Klaas Coulembier wrote this essay for Bozar, in the context of the series Mahler: the symphonies (Belgian National Orchestra, La Monnaie and Bozar).

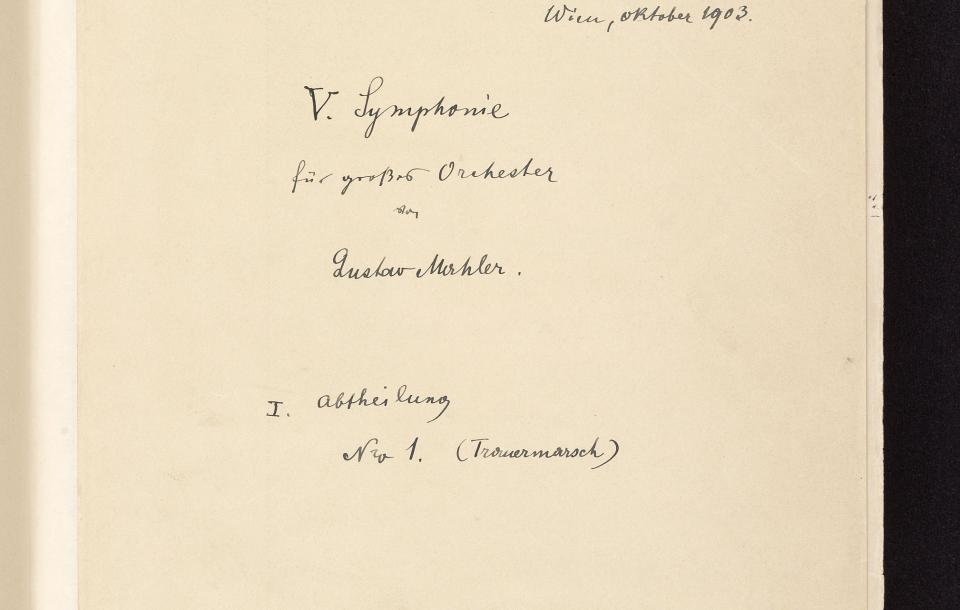

“To my darling Almscherl, the faithful and courageous companion everywhere I go.”

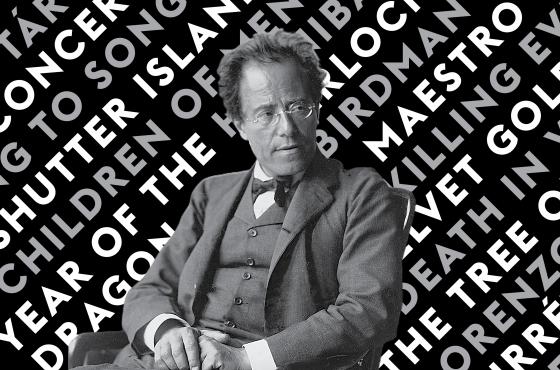

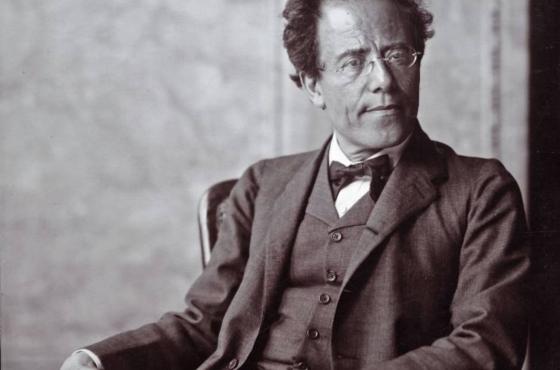

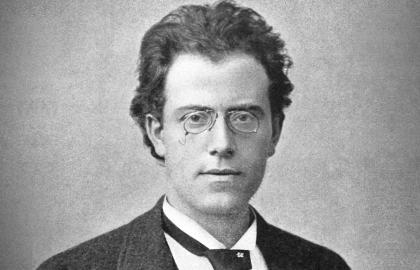

Gustav Mahler wrote these words on the flyleaf of his Fifth Symphony in 1903. He was enjoying the happiest time in his marriage, after his wedding just two years earlier to the beautiful young Alma Schindler, the daughter of a respected landscape painter and a singer. He was also scaling great heights in his professional career. Since 1897, he had been the director of the Vienna State Opera, where he had introduced many innovations (see also the essay by Eline Hadermann). He was a respected figure who alternated his career at the opera with creative periods of composition in the quieter summer months.

Alma Schindler: composer, muse, femme fatale?

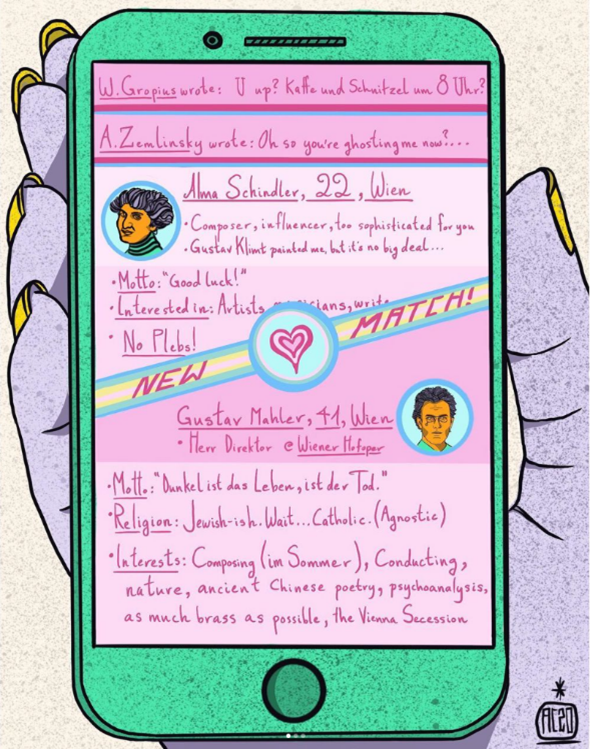

Gustav was not Alma’s first love, and neither would he be her last. After a brief, amorous encounter with Gustav Klimt that was severely condemned by Alma’s mother, the first person that Alma wrote about in her diary with love and desire was the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky. Zemlinsky, who also counted Arnold Schönberg among his students, was a talented young musician in Vienna. The relationship between Alma and Alex, as she called him in her letters, was not without its problems. Zemlinksy’s lower-class origins (and his appearance) did not make him the ideal partner for Alma, who enjoyed a certain public status even then. When she met the flamboyant and reputable Gustav Mahler in 1902, she was faced with a difficult decision. Her diaries relate how she weighed the two men up against each other, wondering whether a marriage to Gustav Mahler would offer her the same as a marriage to Zemlinsky. In the end, she opted for Mahler, at which point her career as a composer took a crucial turn. Whereas Zemlinsky admired and praised her music, Mahler only ever showed a passing interest in her lieder and chamber music.

When Gustav Mahler made it clear to his fiancée in a now-famous letter that there was only space for one composer in their marriage – and there is no question as to which of them that would be – Alma faced a stark choice. She could follow her artistic aspirations and call the wedding off, or choose Gustav Mahler and a life in the service of his music. However, the latter option would not necessarily mean a life in the shadows, devoted merely to the concerns of the household that were a woman’s work by definition at that time. By consenting to the marriage, she exchanged an uncertain future (for a woman) as a composer for the role of muse and patroness of the arts. In the social context of early 20th century Vienna, she might even have had a greater impact in that role than she would have had as a composer.

In the course of her turbulent life, Alma would inspire more than one artist. Looking beyond the juicy details (in her own memoires as well as the countless stories of her life), we see a charismatic woman with the ability to enchant artistic men. During her marriage to Mahler, she also had a relationship with the architect Walter Gropius. That affair was one of the heavy blows that Mahler suffered in the last years of his life, along with the loss of his daughter and his diagnosis with a severe heart condition. After that affair, Mahler also reconsidered his earlier view of her activities as a composer, helping her to publish some of her lieder after all. Legend has it that a consultation with none other than Sigmund Freud persuaded him that he should support Alma’s artistic practice if he wanted to win his wife back entirely for himself. In 2010, Felix and Percy Adlon made a film based on this story.

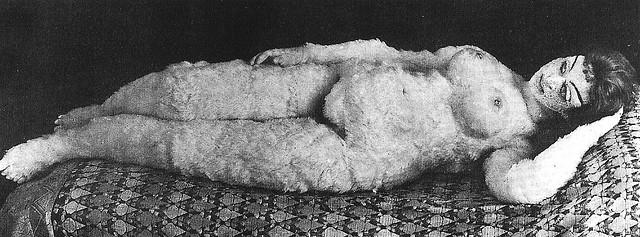

Cover of the publication of Four Songs in 1910. The cover was designed by Oskar Kokoschka, who after the break-up with Alma had a life-size doll made in her likeness.

After Mahler’s death, Alma had a passionate but turbulent relationship with the artist Oskar Kokoschka. More than four hundred love letters testify to an almost obsessive love, but especially also to great jealousy on his part. When Alma left him after three years because the relationship had become untenable for her, he had a life-size doll made in her image, which he initially adored as if it were Alma herself. Ultimately, though, he would destroy the doll in a fit of madness.

After that, she married her former lover Walter Gropius, only to divorce again five years later. Her last and longest marriage was to the writer Franz Werfel, whose surname she continued to use along with Mahler’s. Although their marriage soon became fairly cool and businesslike, she did emigrate to the United States with him in 1938. Germany’s annexation of Austria and the increasing influence of Nazism made it too dangerous for them, along with many other Europeans, to stay. Franz Werfel died in Beverly Hills in 1945. Alma lived as a widow in the US for almost another twenty years, until her death in New York in 1964. She was 85.

Alma’s legacy and ‘The Alma Problem’

Because she wasn’t particularly concerned with historical accuracy herself, destroying or altering many original letters and documents, a veil of mystery has always surrounded Alma’s life. Musicologists speak of ‘The Alma Problem’: the fact that her biography and the many stories about her lovers are mainly based on one subjective, unreliable source. This often leads to contradictions. What makes her life story even more complex is the fact that she actually had antisemitic ideas, despite associating with various Jewish men throughout her life. What is certain is that she left no one unmoved, and that she continues to intrigue people today, as testified by the film mentioned above. Another random example is this drawing by Andrew Crust, a conductor and artist who shares works with a cultural, often musical basis on his Instagram channel “@stick.and.brush”.

And what about Alma’s music? It has gradually been rediscovered over the last few decades. We know that she composed more than 100 songs and a few orchestral works. She also started composing an opera, her ultimate dream as a young composer, but she was never able to finish it. She destroyed most of the scores herself, or else they were lost in the tumult of the Second World War. What remain are seventeen engaging songs that have nothing in common with the style of her husband’s music. In fact, she didn’t like Mahler’s music at all, feeling more drawn to the aesthetic of Brahms, Zemlinsky and her great idol, Richard Wagner.

Last year, the soprano Elise Caluwaerts recorded Alma Mahler’s seventeen songs in Henry Le Bœuf Hall at Bozar.

Mahler’s Fifth: a symphony drenched in marital bliss?

The first notes of the Fifth Symphony don’t sound like the soundtrack to a happy and prosperous marriage. It is only in the course of the successive movements that the biographical context of the symphony can be more or less deduced from the score – to the extent that the symphony should be interpreted biographically at all. In fact, the first of the five movements begins as a sort of funeral march, with a sombre trumpet motif.

Listen to the first part of the symphony, played on the piano by Gustav Mahler

When the finale of the symphony begins an hour later, only words such as energy, euphoria, glory and intense joy suffice. The route to that destination takes us through a stormy second movement full of surprises and a scherzo that winds its way among carefree dance melodies – with the Viennese waltz never far away – and stirring rhythms. After all that excitement, it is time for the calm of the fourth movement. This famous Adagietto – put to magnificent use by Visconti in his film of Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice – is a pure and sincere declaration of love to Alma. Besides creating a beautiful, captivatingly slow movement full of love and tenderness, Mahler also slips a few musical messages into the score that were clear as daylight to her. For example, the opening melody contains a reference to the ‘love glance’ motif, one of the many leitmotifs in Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde. Alma had been fascinated by Wagner’s music from an early age, and she knew his scores like the back of her hand. It is said that she could play the whole opera off by heart on the piano.

See and hear the motif from Tristan und Isolde here and compare it to the opening melody of the Adagietto.