The dream of ‘a house with a garden’ is rooted in history. In the nineteenth century, modernization stimulated a growing need among the moneyed bourgeoisie for a place where they could leave the stresses of modern life behind. This led to a real ‘garden hype’ in which the flower and plant garden took centre stage. It is in the garden that the bourgeois cultivated their free time. To them, it meant the opposite of work. This free-time utopia is amply demonstrated in the garden paintings made by the impressionists. These paintings are almost exclusively populated by women and children, the family members who did not have to work. Thanks to the professional success of the man of the house (often the painter himself), they could retire to the garden and give themselves over to idleness.

Because the garden is not just for resting but also stands for a philosophy of life, it is important that it permeates the entire sphere of life. That is why the impressionists also worked on decorative projects that brought the garden indoors. The most radical realization of this ‘garden room’ idea is to be found in art nouveau, whose entire formal idiom is determined by the unpredictable elegance of nature. The interior space itself is transformed into a ‘garden room’.

Today, the flower garden is still popular. At the same time, the bourgeois garden utopia has taken on other forms. Kitchen gardens have become more fashionable and in recent decades they have grown into a favourite pastime of the well-off middle class. The ideal of a life in harmony with nature is increasingly being translated into a plea for an ecological gardening practice that, instead of seeking to control and exploit nature, is based on a harmonious relation between nature and humankind.

Anne Daems’s Garden Room installation in the Council Room of the Centre for Fine Arts starts from this contemporary garden utopia. The artist adopts the position of a ‘modern’, environmentally aware gardener who specializes in biological and ecological gardening. Organic waste is carefully kept and brought to the compost heap, where worms convert it into fertilizer. This gardener keeps a close eye on slugs which, as no pesticides are used, risk devouring the harvest.

Indeed, ecological gardening is not just a hobby, it is an actual philosophy. The gardener wants her gardening practice to reflect on her entire living environment, in accordance with the old idea of the garden room and today’s lifestyle recommendations. In this, however, she notes an inconsistency. The impressionists and the art nouveau architects were right when they imported a world of floral beauty and decorative plant growth into their interiors. After all, the garden with which the haute bourgeoisie showed off was a decorative flower and plant garden. Today, things are different. The garden has undergone a profound evolution.

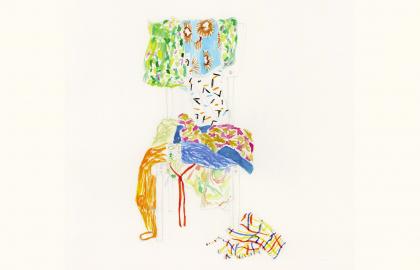

And so the gardener decides to bring into her interior, not the flower garden, but the actual garden, complete with foul-smelling compost heaps, wriggling worms and fiendish slugs. Vegetable leftovers are placed on small clay plates resting on low tables decorated with floral watercolours – because flowers do still grow in her garden. Around them are folding screens, inspired by the ‘byobu’ or ‘wind walls’ that mark the place of the tea master in the Japanese tea ceremony. However, they are not covered with traditional wooden wickerwork or (soberly decorated) Japanese paper as in the tea ceremony, but with ‘(post-)impressionist’ painted watercolours of a compost heap with vegetable remains (on the outside) and worms wriggling around in it (on the inside). Hanging on the side walls are watercolours depicting slugs winding across the white paper as they crawl towards flowers. A pencil drawing on the back wall hints at the plinth and the three original, two-part folding doors – identical to the door leading into the exhibition space – which are hidden from view by this false exhibition wall. The plinth and the door complete the illusion of a bourgeois interior. At the same time, they form an imaginary ‘back door’ that opens the room onto an imaginary dream garden. Watercolours depicting exuberantly coloured items of clothing thrown over the back of a chair let the outdoor world of the garden enter the bourgeois room like sunlight.

The watercolours of compost and low animal species as well as the sculptures of vegetable waste infect the traditional image of the garden room with a world that can evoke repugnance and disgust. The depiction of this worm-eaten universe on wind walls is almost like a blasphemous joke. However, this is contradicted by the earnestness with which the gardener devotes herself to the garden room. The watercolours have been painted lovingly, in carefree strokes and with a light, sun-kissed palette. The vegetable leftovers have been ‘draped’ with great delicacy on the small plates, as though they were precious items. The Japanese wind walls suggest that this fermenting ecosystem should be treated with the same respect and attention that the tea master pays to the preparation of the tea. There can be no question of cynicism. The gardener is convinced that this world of crawling creatures and stinking substances deserves to be appreciated and contemplated. This is not illogical: after all, for amateurs of ecological gardening, worms do not bring death and decomposition to mind, but the magical ability to transform that which dies and decays into a source of new life. The wind walls suggest that the gardener is strengthened in this conviction by the Taoist thinking underlying the Japanese tea ceremony. The tea ceremony revolves around ‘the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence’, we read in The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura (1862–1913). This description, the gardener must have thought, is perfectly applicable to worms and compost heaps. This also helps to explain the ritualistic earnestness with which she surrounds her garden world and which brings to mind the devotional culture around the ‘hortus conclusus’ (enclosed garden) and the ‘Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Tuine’ (Our Lady of the Garden).

But what about the slugs? It is rather difficult for the gardener to appreciate these vermin. The worst part is not so much that they threaten the produce of the garden, but that they force the gardener to break her harmonious relation with nature. Indeed, she must kill the slugs to preserve her ecosystem. This painful measure confronts her with the sad realization that humankind remains more than ever caught in the ‘dialectic of mastery of nature’.

Is Garden Room, then, a critique of the ideology of ecological gardening – and of all kinds of promises of well-being in general? Again, the beauty of the watercolours seems to refute this. The light, ‘impressionistic’ touch is restrained by the elegant serpentine lines of the slugs. The use of the sheet’s white space is reminiscent of traditional Japanese painting. So much meditative respect for and aesthetic homage to the vermin that collapses the whole garden utopia …

With a great sense of absurdity, Garden Room looks at the way in which humankind in the West labours on its well-being, but the sincere, melancholy and meditative beauty of the installation leaves open the possibility that something ‘good’ may yet be distilled from this culture of wellness. Maybe wellness can be meaningful after all if you take it ever so seriously . Could such a thing as ‘dystopian wellness’ exist?

Dirk Pültau