Not many European art centres of international stature organise annual multidisciplinary events dedicated to the African and Afro-descendant art scene. In the past ten years or so, an increasing number of events focused on African artists are taking place in Europe, but these are mostly limited to a specific artist, art form, or country, or are then larger, but one-off, events. Sustained, cross-disciplinary platforms in cultural institutions are still the exception.

Between hope and distrust

Thus, undoubtedly, the Afropolitan Festival initially engendered both hope and caution in the Afro-Belgian cultural realm. Artists and cultural organisers were openly dubious and wary as soon as preparation of the festival’s first edition – Afropean+ in February 2015 – was underway. Can the Centre for Fine Arts of Brussels, an iconic Belgian institution considered to be prestigious and elitist, broadly embrace the local and European Afro-descendant art scene? Why such an approach? Is it cause for rejoicing or distrust? Is there a hidden agenda to such a novel decision?

It should be noted that the festival’s first edition was not organised at BOZAR’s initiative, but was instead the idea ofCongolese artist Pitcho Womba Konga, a rapper and theatre actor who lives in Brussels. He suggested the concept of a “Congolisation” festival, an event meant to pay tribute to Patrice Lumumba, an iconic figure of Belgian Congo’s independence, the country’s Prime Minister who was assassinated in 1961, and its national hero.

Our purpose is not to review the history of the event’s first edition, which was held at BOZAR on 17 January 2015 (the anniversary of Patrice Lumumba’s assassination)[1], but to recall the origins of the Afropolitan Festival and to fully grasp one of the major aspects that defines it: the profound political dimensions of its artistic performances and their portrayal at an iconic public cultural institution.

Artistic performances in keeping with the African diaspora experience

The African and Afro-European art scenes are increasingly “in vogue”, particularly in Europe, due to their level of excellence, their flourishing creativity, and a sense of urgency that is generally compelling to the Western world. In the past fifty years, African and Afro-descendant diaspora communities have grown in the former major European colonial powers. It is currently estimated that 8 million Afropeans live in Europe, 500,000 of whom in Belgium[2]. Many of these Afropeans either have dual citizenship, or have become citizens of their adoptive country while fostering strong ties with their native country.

This duality is one of the characteristics of Afropolitanism, a concept defined by political theorist Achille Mbembe: “Today, many Africans live outside Africa. Others have decided of their own accord to live on the continent but not necessarily in their countries of birth. More so, many of them have had the opportunity to experience several worlds and, in fact, have not stopped coming and going, developing an invaluable wealth of perception and sensitivity in the course of these movements. These are usually people who can express themselves in more than one language. They are developing, sometimes without their knowing it, a transnational culture which I call ‘Afropolitan’ culture.” [3]

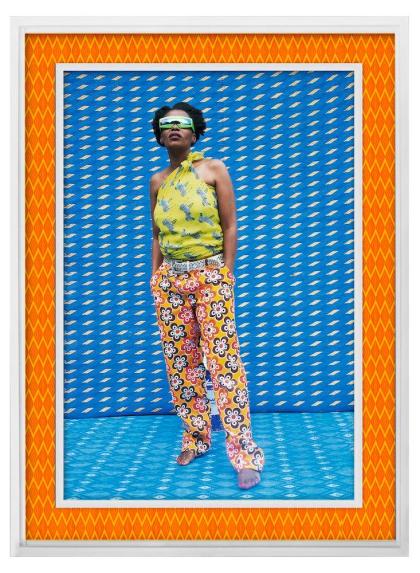

The Afropolitan Festival, as its name implies, aims to celebrate Afropolitan culture. A culture that is far from uniform, whose aesthetic expression, and message, are highly diverse, and whose actors share the same purpose: an unfettered (re)presentation of their unique stories.

For too long, the artistic expression of African diasporas in Europe have suffered from invisibility. Until recently, they were restricted to community-type venues and did not attract interest from major European cultural institutions. And yet, these expressions have always existed; different ways of portraying the “Afropolitan experience”, whether it be exile, racism and discrimination, or invisibility; but also, solidarity, the struggle for emancipation, or the weight of individual responsibility. Complex Afropolitan identity, marked by colonial and postcolonial history, is and has always been at the heart of these artistic expressions.

Throughout the four editions of the Afropolitan Festival, the political dimension of the programme’s events is clearly apparent, whether it be in films, performances, debates based on readings to foster reflection, or personal stories.[4] The political dimension has a particular reverberation when the performances that convey it are held in a prestigious European cultural institution. It prompts us to question the place that the institution reserves for Afropolitan expression and its capacity to drive artistic and social change.

A process for reciprocal legitimacy

The Afropolitan Festival aims to grant greater visibility to European Afropolitan artists and intellectuals. The event has, nevertheless, been confronted with several artistic and social challenges from the start. Aesthetic considerations have prompted reflection on the latitude that an institution such as BOZAR can demonstrate with regards to a different or fringe aesthetic that is not necessarily in keeping with its foremost criteria of excellence. Whether it be urban and improvised dance forms (such as hip-hop performances by Les Mybalés in 2017, Bintou Dembele in 2018 and Cal Hunt in 2020) or the Afropean Project “moving debates” in 2017 and 2018, the festival brings an alternative, hybrid aesthetic to the institution. As a result, it contributes to a more diverse event calendar at the Centre for Fine Arts, and prompts a shift towards more inclusive and permeable artistic boundaries. It thus contributes to “desacralizing the Western paradigms of art", to use the expression of the philosopher Jean-Louis Sagot-Duvauroux[5].

This dual process enhances both the artists and the art institution. On the one hand, due to its reputation as an art centre for excellence, and its international reach, BOZAR undoubtedly confers value to the artistic performances that it presents. On the other, the African and Afro-descendant aesthetic provides the Centre with a richer artistic programme, while prompting reflection, fostering openness and embodying a contemporary feel in line with today’s postcolonial and multicultural societies.

Nowadays, event and audience diversification are key challenges for cultural institutions. The Afropolitan platform is one way in which BOZAR is moving towards diversity. It is a means to engender lasting openness to new art scenes, and to expand and diversify its audience, especially by attracting Afro-descendants and African nationals who, prior to the platform’s creation, seldom attended events at the Centre for Fine Arts.

What constitutes the core? Where are the boundaries? It is a fact that the cultural landscape is not exempt from the power struggles and race domination that African and Afro-descendant diasporas experience in western societies. It is, nevertheless, a space where such struggles can be expressed and reassessed. Cultural institutions remain places which influence and grant artistic legitimacy. They need, however, to mirror their multicultural environment and to demonstrate that they are attuned to avant-garde artistic expressions, whether monochromatic or ethnically diverse.

Co-creation and decolonisation

The festival is an artistic and social platform for reciprocal legitimacy. On the one hand, African and Afro-descendant artists may consider it as a form of artistic and social recognition; on the other, it is a means for the cultural institution to portray an open artistic and social approach and its desire to promote inclusiveness.

In the very early stages of the festival’s preparation, Afro-descendant artists and cultural organisers advocated for a comprehensive co-creation process. The popular term stands for a methodology approach in which designers have equal status when organising or producing an event, which respects the specific character and interests of each partner. As most African and Afro-descendant organisations and groups are struggling, this methodology is meant to help them establish more egalitarian relationships with the art centre. Opting for a co-creation process, however, is not sufficient. It takes time and requires learning, and evolves through listening, mutual respect, and the fine art of compromise. The process requires all stakeholders, particularly the institution, to practice self-assessment and to be truly capable of transformation.

BOZAR and its festival partners are committed to learn and implement this methodology. Certainly, it is not straightforward. The institution’s own culture and practices sometimes differ greatly from those of Afro-descendant organisations and artists. Stability versus insecurity, rigidity versus responsiveness, rules versus improvisation: making two different realities coincide is not always easy. It is striking to realise, however, how a long-term project is paramount to strengthening and gradually decolonising all partners.

For this reason, BOZAR started the Afropolitan Forum in 2019, a five-year programme that focuses on artistic and cultural expression, research and debating of ideas pertaining to Afropeans in Belgium and Europe. Created through a partnership between the Africa Museum and the Brussels Centre for Fine Arts, and financed by the Belgian development cooperation, the programme aims to specifically bolster the co-creation process and establish increasingly inclusive and sustainable collaboration. In keeping with the Afropolitan Festival, it also helps to dismantle preconceived notions and stereotypes about Africa and to drive change in perceptions, values and mindsets. It functions particularly through yearly calls for proposals[6].

The Forum programme and the Afropolitan Festival are designed to function as complementary entities that foster short- and long-term synergy with each other, and aim to establish a novel and lasting platform for local and international Afropolitan artistic creations. As one of BOZAR’s major ambitions, the Centre is eager to see similar platforms emerge in Europe and Africa in the near future.

Furthermore, the transnational networking effort also includes the setup of a festival platform as part of the 2020 Afropolitan Festival. Its goal? To bring together Afropolitan festivals and biennials in Europe and Africa to promote spontaneous collaboration and exchange between event founders or directors, art institutions in charge of cultural cooperation, and diverse audiences. To develop and strengthen artistic and social recognition, it is in the best interests of Afropolitan festivals and biennials to establish an international network.

By 2050, Africa will account for more than a quarter of the global population. Achille Mbembe and other African intellectuals believe that this change will coincide with an “Africanisation of the world”. Afropolitan festivals and biennials will have undoubtedly contributed to the world’s Africanisation and to decolonising societies and public imagination. The Afropolitan Festival is determined to take on this artistic and social role, and to pursue its reflection and practices with its partners, artists and intellectuals, activists and audiences. Join us on 18 to 21 February 2021, at the Brussels Centre for Fine Arts, for the festival’s fifth edition, which will focus on “Women’s power”.

Ayoko Mensah, Afropolitan Festival curator

[1] To read more on the topic, several articles are available such as: https://zintv.org/qui-a-peur-de-lumumba/

[2] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afro-Europ%C3%A9ens

[3] In “Afropolitanism, the way Africans make, manage and irrigate the world”. Achille Mbembe interview. Illmatik issue n°1. 2015. www.illmatik.com

[4] More about the festival’s different programmes: https://www.bozar.be/en/search?q=Afropolitan%20Festival

[6] https://www.bozar.be/en/news/167430-call-for-projects-afropolitan-forum