This exhibition comes 20 years after your first solo at BOZAR – what are your memories of that first exhibition?

Du mentir-faux was above all my first solo exhibition in Brussels, the city that has been my home since 1986 when I arrived here to study film at Sint-Lukas. I have very vivid memories of it. It was the first time I had worked with slide projections, with an exceptional actress who died a year later from leukaemia. In August 1999 I myself had a serious fall from a ladder that landed me in hospital for three months. Du mentir-faux, the installation and exhibition of the same name, was my first project following that accident.

And your first memories of BOZAR?

The first memory must be Au Coeur du Maelstrom/In de Maalstroom (1986), the farewell exhibition for Karel Geirlandt, director at the time of the Exhibitions Association at the Centre for Fine Arts. This was put together by, among others, Chris Dercon, who was one of my teachers at Sint-Lukas in Brussels at the time. It was at this exhibition that I first saw the work of James Coleman, Living and Presumed Dead, and that made a big impression on me.

I also recall the exhibition of the work of Jan Vercruysse (1988). This was the first time I saw one of his complete “atopies” series. Then there was the wonderful exhibition Azetta (2000), about the art of Berber women, with scenography by Zaha Hadid. That really stayed with me. But I also very clearly remember the exhibitions by Franciska Lambrechts, with a wonderful film installation (Dialogues, 1996), as well as the one by Elaine Reichek with her embroidery (Thuis en in de wereld, 2000).

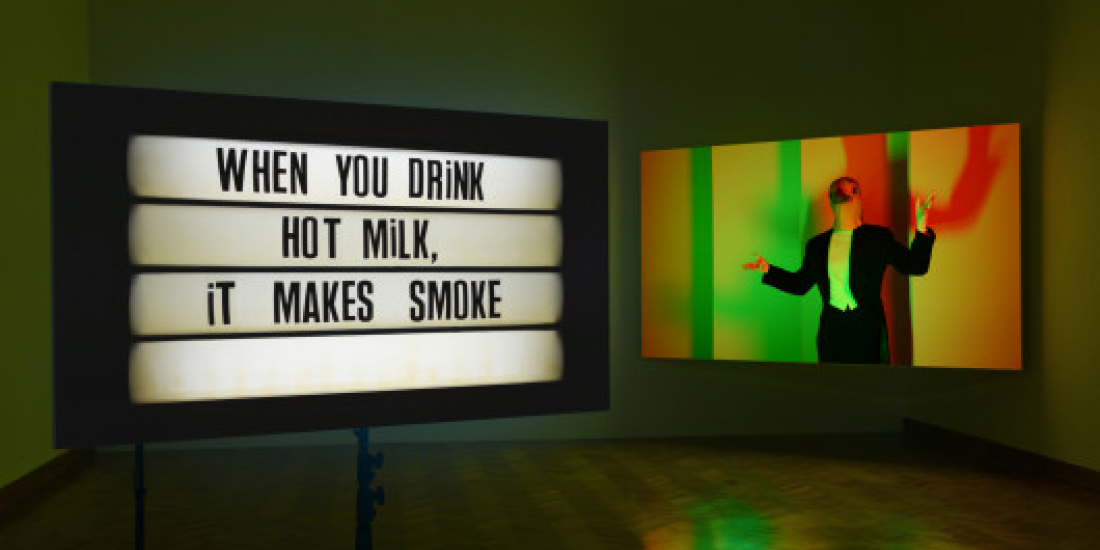

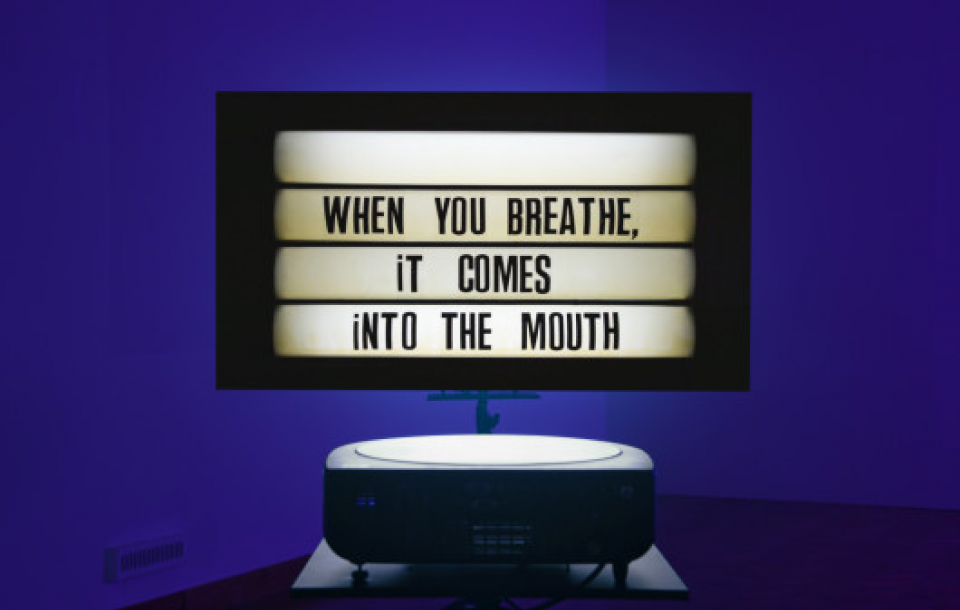

The first installation we encounter in the exhibition is When You Whistle, It Makes Air Come Out (2019), which has a fascinating and surprising source.

Sometime at the beginning of 2018 I read the book La causalité physique chez l’enfant (1927) by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, which must have really fascinated me as during the Easter holidays I already set to work using an old light box, introducing the letters one at a time to form the words. The answers given by children to questions such as ‘what is the wind made of’, ‘where does the wind come from’, ‘what happens when you blow’ or ‘where does the air in your mouth come from’ are both innocent and surprising.

I added my breathing to the montage a year later. This breath is important, the breath of the artist that brings dead things to life. Literally through this breath of life, but also through the animation technique of the photographic images in Sideshow (2019). This technique is also found in the work The Shadow Is Black and in the Darkness It Can’t Show (2019), where a person dressed entirely in black tries in vain to bring a puppet to life.

Echo's long monologue which we can hear in Echo’s Bones/Were Turned to Stone (2020) consists of a wide range of almost countless references. Can you say something about the method of working in which this web of references came about?

For years I have been collecting fragments of text, in the course of my reading. Always with the desire to do something with them. Juggling all these notes is a genuine writing process, even if it all consists of texts I have found and have ordered in an anaphoric way, where repetition plays an important part.

It is also important that it is not just text. It is a monologue for a female voice (the actress Caroline Daish) who brings the text to life. It is a character who sighs and groans as she relates her endless accounts with anecdotes from the lives of dead artists, composers, writers and film directors. It was in 2016 that I made the first notes for this monologue.

I don't think I have ever spun such a wide web. I had wanted to get back to writing for some time, as in a work from 2002 (Elective Affinities/The Truth of Masks & Tables of Affinities) where the text lay like a kind of "book in the making" on reading tables. Now I wanted to literally bring the text to life through a voice. The nymph Echo from Greek mythology, who could only repeat what others said, is essential for an understanding of my work: the repetition, the role of the voice, the use of existing texts and sometimes also images.

A notable result of the COVID-19 crisis and the measures taken was that we were shaken from our routine. We were obliged to step down from the daily rat race. That is also something that art does - and your work in particular. In a sense it imposes its own experience of time on the spectator. Is this ‘time bending’ something you do consciously?

I have never really stopped to think about it. The slowness is present both in the work itself and in my own process. I need time to make something. There is a lot of trial and error. I like to allow things to crystallize slowly in a very organic and associative way. When I start something, I never know where I am going to end up and a work can still be evolving almost until the time of the vernissage…

During the lockdown you started a wonderful Instagram account. It seems like a perfect place for an artist who clearly loves to explore a sea of information and references, discoveries. But "instant" is not a term that we associate with your carefully thought out work. How did you find it there?

I probably first started on Instagram due to the vacuum that followed the closing of my exhibition The Magician & the Surgeon just a day after it had opened.

‘Instant’ is indeed not something that comes naturally to me… There are fascinating things to see on Instagram, but I am still not sure what I should do with it.