"Doesn’t Joëlle Dubois paint people having sex?” My ear catches the question coming from a couple sitting in front of me whilst I am tapping on my phone. I don’t hear the answer as a group of teenagers, with a self-confidence and sense of style I wished I had at their age, loudly gets on the bus. Everyone’s attention shifts towards them, and I miss my opportunity to crash the conversation and say “Yes, but actually no, because she paints the archetypes of our times and it’s dark!” Instead, I sit quietly in my seat.

Belgian artist Joëlle Dubois is known for her vibrant and colourful paintings depicting explicit sexual intercourse, intimidating women, and fragile and lonely individuals who are absorbed by their computer, tablet or smartphone. Behind the candy-coloured 80s Miami Beach vibe and explicit erotica, Dubois portrays symptoms of contemporary life, including our dependence on social media and technology, and how both have shaped our intimate relationships and love practices, beauty standards and self-confidence.

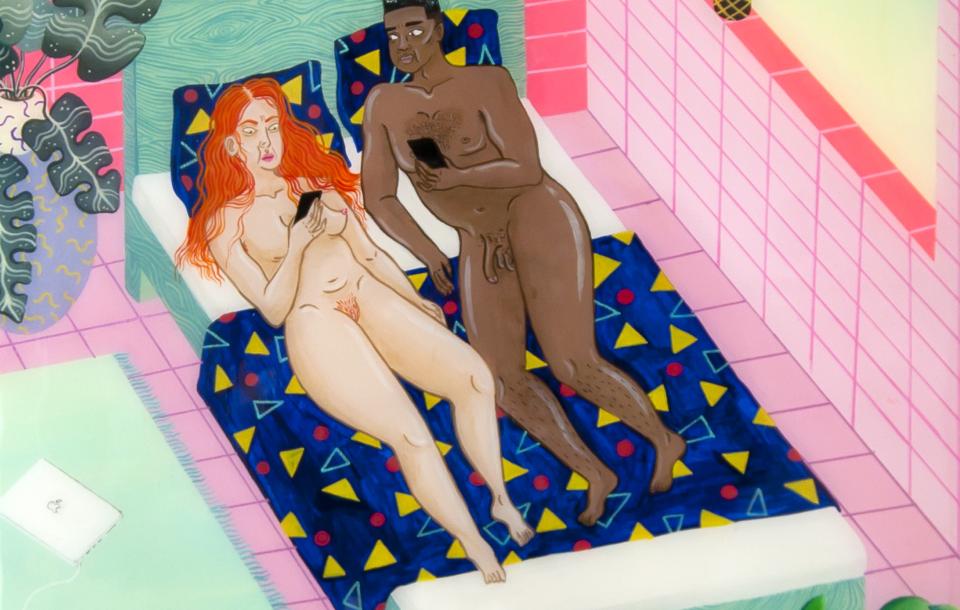

Dubois is a storyteller who turns her personal experiences into paintings, shamelessly and fearlessly. Though you’ll soon notice that her stories (and paintings) are easily relatable. In According to Lulu He Has the Smallest Dick Ever, a couple is seen resting on a bed in what we assume is a post-coital moment. The sexy and revealing red lingerie, the half-consumed candles, the empty cans of beer and the weed on the table suggest we are witnessing the aftermath of a steamy night of love-making. But upon closer inspection, Dubois’ erotic scene exudes little intimacy. The woman is absorbed by the content on her phone, while the man is observing her with a worrying look. As the title suggests, she is probably discussing the size of his penis with her girlfriends. Or is checking an app for her next mate? A coldness sets in, the characters’ physical proximity in sharp contrast to their emotional unavailability.

Joëlle Dubois explores the personal to talk about the universal. Through her paintings, we become witness of new forms of relationship-making of an ultra-digitally connected generation. Assured in body and self, love and sexuality seem to become another transaction where the sexual partner becomes a disposable item – to be replaced with a left or right swipe on the phone if the desired criteria are not fully met. Witnessing the struggles of my single friends in their forties, it seems to me that to navigate dating and relationships has become increasingly incomprehensible since the dawn of social media, dating sites and apps. The puzzlement on the man’s face in Dubois’ painting and the apathy of the woman next to him are depictions of a type of relationship that contemporary sociologists call ‘situationships.’ Neither a romantic relationship with a clear courtship, nor one with a duration in time, a situationship is an emotionally detached interaction between consenting adults who engage in casual sex. The non-relationship can end at whatever moment. No explanation needed.

There is a certain liberation in no-strings-attached sex, especially for women nowadays. But that is not to say that it doesn’t also come with a certain melancholia. The contemporary erotic and sexual experience as shaped (and documented) by social media might be fun, quick, ego-satisfying and responsibility-free. But quite often, under its shiny surface, loneliness lingers. And it is that loneliness that Dubois’ work pinpoints in this era of fast love and consumption.