© John Baldessari 1973. Courtesy Estate of John Baldessari © 2025; Courtesy John Baldessari Family Foundation; Sprüth Magers; Craig Robins Collection, Miami

1. Having a ball

In the 1970s, photography became Baldessari’s principal medium – not as a means of producing perfect images, but as a way to see what happens when you try to capture the impossible. In Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (1973), he simply tossed three balls into the air, thirty-six times in succession, in an attempt to create a straight line. The bright Southern California sky was his canvas, the camera, his witness.

The result is not a carefully composed artwork but a game of chance, control and failure. Baldessari does not turn his lens towards beauty, but towards the process itself: the attempt, the selection, the decision. What survives? What is omitted? In so doing, he challenges not only the conventions of photography but also the very idea of what art must – or can – be.

2. Anything but perfect

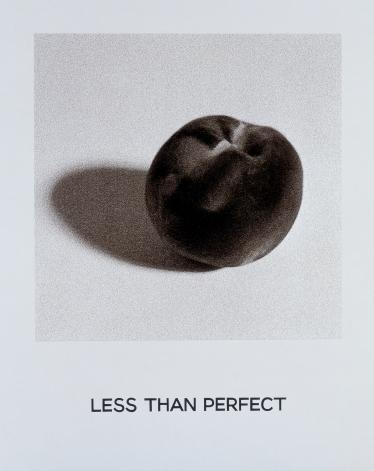

Language is an essential element in Baldessari’s work. In his Goya Series (1997), he fuses image and text into a single whole: twenty-six large canvases, each pairing a photograph with a title that responds to it. For this series, he drew inspiration from Francisco de Goya’s renowned print cycle The Disasters of War, which juxtaposes harrowing scenes with cool, ironic captions.

Like Goya, Baldessari explores the tension between image and language – but with a contemporary lightness. A photograph of a vase of flowers is paired with There Isn’t Time, an overripe peach with Less Than Perfect. Banal images acquire unexpected resonance –sometimes humorous, sometimes wry – and provoke reflection. For Baldessari, image and text carry equal weight.

3. Poetic collision

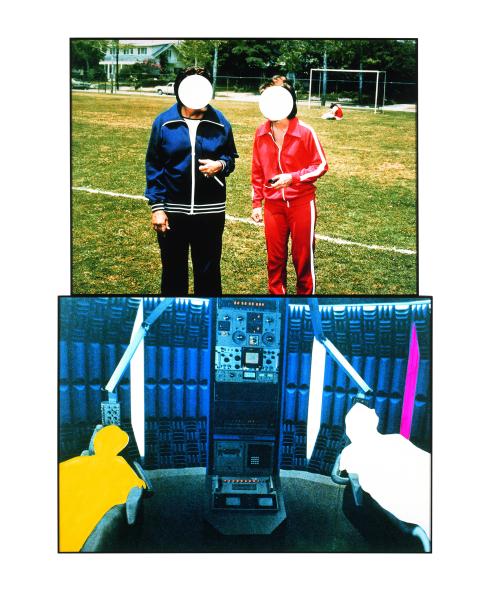

In Two Figures and Two Figures (In Different Environments) (1990), Baldessari combines photography, painting and collage to create an image in which two couples mirror each other: the lower pair is covered in paint, while the upper pair has coloured dots obscuring their faces. The individuals disappear, their identities blur—and suddenly, the background takes centre stage.

“The ‘collision’ is quite fundamental to my work, the collision of different images. In that sense, I consider myself – perhaps somewhat cornily – a poet.”

With interventions such as these, Baldessari strips images of their apparent self-evidence. What happens when you remove the most essential part of a photograph – the face, the gaze? What remains of meaning, emotion or narrative? He likens the act of combining images to poetry: a collision between two elements that are sufficiently different to generate something new.

4. Big, small and everything in-between

From the late 1960s onwards, John Baldessari focused entirely on conceptual art. In Dwarf and Rhinoceros (With Large Black Shape) from 1989, he explores the relationship between humans, animals and space. And especially what happens between those elements.

The installation comprises several life-size photographs. On one side, a grey rhinoceros stands in a dry landscape beside an enlarged, black-and-white image of a small man who, with his finger outstretched, appears to point at the animal. The scale is deliberately distorted, and herein lies the subtle irony: in relation to the rhinoceros, the viewer also seems to diminish in size. Turning around, you are confronted by a large black silhouette of the animal.

In another corner, a similar dialogue unfolds. Two photographs face each other: one depicts a pair of legs atop a pile of books on a chair, the other shows a man from the waist up, standing on a chair and talking on the telephone, his face obscured by a blue dot. The figures’ orientations do not align, and it remains unclear whether the images depict the same person. Here, Baldessari creates not only a visual but also an architectural game: the space itself becomes part of the work.

5. The walls have ears

In 1998, John Baldessari designed a special wallpaper for an exhibition at what was then the Witte de With Centre for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam, now the Kunstinstituut Melly. The work brought the atmosphere of a homely living room into the exhibition space. Art and life meet.

Baldessari designed four variants, each with its own motif: an ear and a pretzel, a nose and pieces of popcorn, a light bulb and a potato, a clock and a pizza. The playful combinations of body parts and snacks demonstrate his typical sense of humour and absurdity. By repeating and juxtaposing recognizable shapes, he creates patterns according to his classic recipe: familiarity and alienation side by side.

The silhouettes of ears, noses and other body parts refer to a recurring motif in his oeuvre: the human body as fragment, as sign. In the context of this exhibition, the wallpaper patterns tie in with Baldessari’s enduring fascination with how the body is portrayed in art — sometimes humorously, sometimes disturbingly — and how new technologies, from photography to digital media, are constantly altering that gaze.