If you read one book in 2022, make sure it's The Dawn of Everything. Even if you are not convinced by the spectacular insights of David Wengrow and David Graeber, you will not escape the urge to seek counter-arguments to their stunning theses. According to them, civilisation did not begin with the invention of agriculture; our idea of freedom is linked to slavery, and it was actually a Native American (Indian) who instigated the European Enlightenment.

Since the publication of The Dawn of Everything, David Wengrow has been running from one interview to the next. On 1 September, he will come to present the book to the audience at Bozar. He has to do this alone as David Graeber, with whom he co-wrote the work, died shortly after they finished the monumental tome.

The Dawn of Everything challenges a range of "sacred cows", including the ideas of the eighteenth-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He believed that, for nearly 200,000 years, humans lived in small but egalitarian societies of hunter-gatherers. With the development of agriculture came more people, which led to complexity, hierarchy, exploitation, but also art and philosophy. Man also lost three fundamental freedoms: the freedom to move around freely, the freedom not to accept orders, and the freedom to choose how to live with others. This theory, according to Wengrow, is not only flawed but also very persistent, as evidenced by the success of a book like Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari.

David Wengrow, Lecturer at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, exchanged his ideas about the origins of inequality with American David Graeber. In addition to being an anthropologist, Graeber was also an activist: in 2011, he set up the Occupy Wall Street protest movement to address economic inequality in America. Wengrow and Graeber initially wanted to write a short leaflet to challenge these stubborn ideas around civilisation, but it quickly grew into a monumental study of over 700 pages. "Our biggest frustration was that we found an enormous number of studies that confirmed our insights, but very few people in our fields had been working on synthesising them. That's when we realised that a little leaflet wasn't going to be enough."

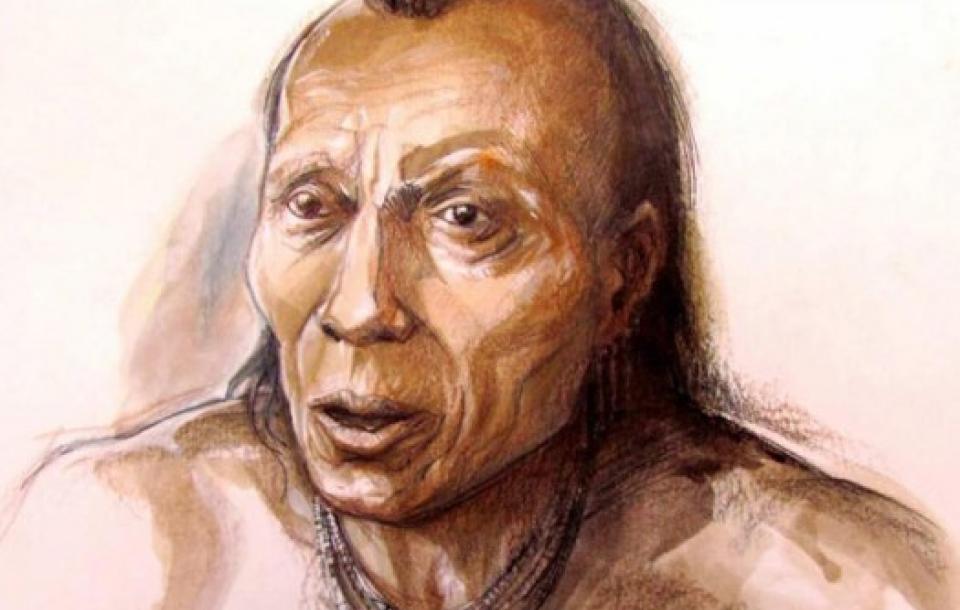

The genius Kondiaronk

On several occasions, the answers to Graeber and Wengrow's questions about inequality came from unexpected quarters. For example, they bumped into the philosopher-statesman Kondiaronk, nicknamed The Rat, who, as a member of the indigenous population around Quebec, exchanged ideas with French missionaries. His conversations with the governor of New France were published and the book quickly became a bestseller that was on every Enlightenment philosopher's bookshelf. A quote from the book reads as follows: “I affirm that what you call money is the devil of devils; the tyrant of the French, the source of all evils; the bane of souls and slaughterhouse of the living.(...) Money is the father of luxury, lasciviousness, intrigues, trickery, lies, betrayal, insincerity, – of all the world’s worst behaviour.”

Forgotten sources

Wengrow explains that sources like Kondiaronk's are often forgotten. This is unfortunate, he says, since they contributed significantly to the confrontation of different philosophical ideas about how societies are arranged. "The great insight of the Enlightenment is that people are able to govern themselves without chaos. That they don't need a god or a king for that. That's still a shocking idea to many people today."

In the nineteenth century, these views were dismissed as utopian and dangerous, argue Wengrow and Graeber. For example, the French economist Anne Robert Jacques Turgot pushed aside this view of societies, using the excuse that they were often small, primitive, and inferior societies that only functioned because everyone was equally poor. This creates a linear thought pattern which sees humans first being hunter-gatherers, then beginning to domesticate animals, and eventually evolving through agriculture and urbanisation to prosperity, but also inequality.

This frame has proven to be very persistent. Those who argue today for a more egalitarian society are quickly accused of wanting to take us back to ‘the stone age’. "When we proclaim that our research shows that it is indeed possible to govern complex societies in a much less authoritarian manner, the word 'anarchy' is quickly used," says Wengrow. "But anarchy is not a synonym for chaos. It is living together without violence and coercion. Our book shows that our ancestors made more than meritorious attempts in the past to do things differently than they do today."

A weird Western concept

What the West defines as "freedom" differs greatly from how people on other continents interpret it, Wengrow and Graeber write, inspired by the work of Jamaican sociologist Orlando Patterson. "We accept that we are free from captivity, free from the authority of a ruler, but we are not bothered that our fellow human beings are imprisoned or slaves. Western freedom is primarily freedom over property. The responsibility to care and share, which is essential to freedom as, for example, Kondiaronk defined it, has been completely eliminated."

"Our freedoms are mostly sham freedoms, but the people who exercise authority over us are indeed powerful," write Wengrow and Graeber. "There are several cases of settlers who were captured by Indians and yet, upon their liberation, did not choose to return to Western society. The research we did on this had a real impact on us."

Hitting a nerve

The Dawn of Everything shot to second place on Amazon's bestseller list even before the book was released late last year. Meanwhile, the book is being busily translated. It's hard to keep pace with the stream of reviews.

"I recently read a review in which someone made the simple point that people who are fleeing today, or people who are imprisoned in their own countries, still come up with the most ingenious ways to hold on to their humanity," Wengrow writes. "They remain active as artists, even though they are at great risk. If people can do this today in conditions of extreme oppression, why should we assume, as Harari writes, that we are stuck in a series of transitions from cage to cage? It is not an innate human instinct to live like a prisoner. Even people living in prison often find incredible ways to be free."

"Perhaps that's one of the reasons our book appeals to so many people: the classical narrative of history makes us feel insignificant and incapable of action. Our book does not prescribe anything. It doesn't offer recipes for a better future and it doesn't tell us where to go. It does, however, try to take the ball and chain off your ankle and say, 'Wherever you go, do not drag this heavy weight around with you'."

On this page, you could read an abridged version of an interview with Wengrow in Apache. You can find the full article here.