Ever since I was little, I have shuddered at the idea of animals being quartered and then displayed naked, as if it could happen to me too. The misleading new shop layout is therefore the only reason I ended up in this aisle. Of course, I could walk through without looking, ignore the battlefield, but I slow down and scan the display cases one by one. The meat products look deceptively peaceful – tender and tasty – and for a moment I think back to summer barbecues and lavish endings to nights out. I gave up eating animals years ago, but Ocean Vuong is right: it’s hard to resist what is presented so deliciously and pushed under your nose.

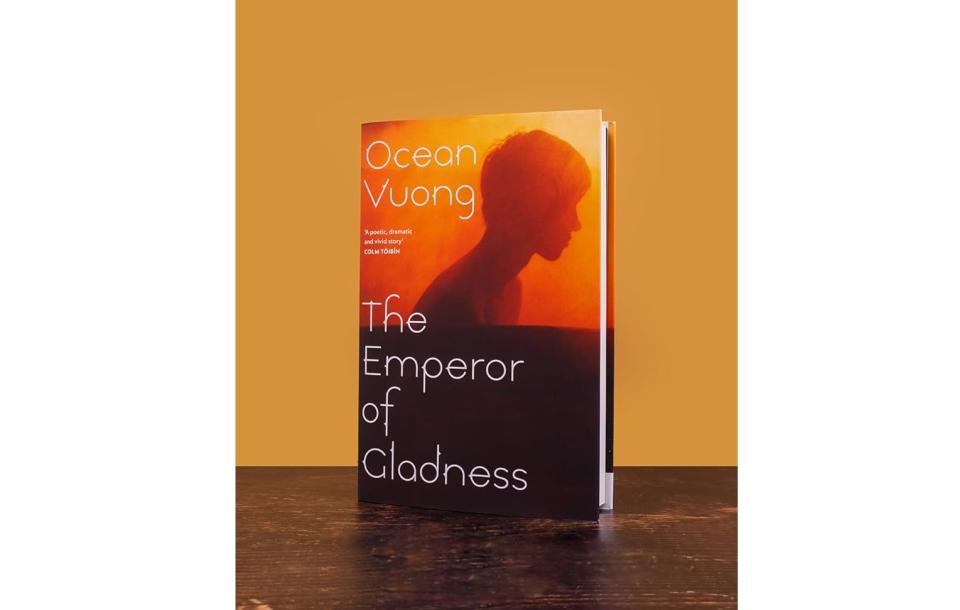

Vuong’s new novel, The Emperor of Gladness, can be read as an in-depth critique of the food industry – a mirror of the suffering that people inflict on each other, as the author explains in the podcast Oprah’s Book Club. Via the fictional fast food restaurant HomeMarket, where most of the story is situated, he portrays the mass production and artificial nature of ultra-processed food.

Vuong is equally harsh on meat labelled ‘ethical and organic’. Halfway through the book, the protagonist Hai travels to a ‘free-range’ pig farm, together with several HomeMarket colleagues. Wayne, who roasts chickens at work, has asked them to help him package meat over the weekend. What seemed like an easy and well-paid extra job turns into a bloody hunting and slaughter scene in the barn. The only access to the outside air is a narrow run on the side, so small that none of the pigs have ever been able to use it.

In addition to the food industry, fabrications are also omnipresent in the characters’ personal lives. Hai insists to his mother that he is studying medicine in Boston, Auntie Kim persuades Hai’s cousin Sony that his father is still alive, and Hai’s colleague Maureen is convinced that the world is ruled by subterranean reptiles that feast on human suffering. Time and again, the characters weave stories to protect themselves, to keep going, or to avoid disappointing others. In short: to survive. Beauty softens what is too raw to look at directly.

At the same time, Vuong shows that beauty is not restricted to the seemingly perfect. The harsh working conditions and simmering despair turn the HomeMarket crew into a self-chosen family, in which Russia, despite his Gollum-like appearance, arouses desire in Hai. East Gladness, the fictional and post-industrial city where the story is set, acquires a magical and picturesque glow, despite its roughness. And then, of course, there is the relationship between Hai and Grazina, the elderly and care-dependent Lithuanian woman, who choose to save each other.

As in his poetry collections and debut novel, Ocean Vuong once again shows how human life constantly teeters on the brink of disruption. His work is deeply influenced by his background. Born in Vietnam and raised in a poor suburb of Connecticut, he learned early on that violence and vulnerability are deeply enmeshed. This sensitivity culminated in his acclaimed debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, written as a letter to his illiterate mother. It is a coming-of-age story, but also an attempt at healing: Vuong explores how identity is formed in the shadow of trauma, poverty and migration, and how love can assume an unexpected beauty in these very circumstances.

Vuong makes this ambiguity even more explicit in The Emperor of Gladness: beauty and cruelty are not opposing forces, but two sides of the same coin. They shape lives in tandem, especially those of people in vulnerable or minority positions. Vuong demonstrates how ethnicity, social class and sexuality are not just themes, but structures within which every form of intimacy must be regained. Consequently, every personal moment remains embedded in a broader, often bleak American reality. This layering is already apparent in the opening sentence: “The hardest thing in the world is to live only once. But it’s beautiful here, even the ghosts agree.” That single paradox – that life is painful and yet glitters – may well be at the heart of Vuong’s writing.