The exhibition explores beauty as both a system of oppression and a force of emancipation. “Beauty is a relational force, a vehicle for emancipation, but it also has a dark side that puts pressure on the body and young people and, above all, leads to hypersexualization – primarily, though not exclusively, of women,” says curator Christel Tsilibaris.

Picture Perfect unfolds in two parts: deconstruction and recuperation. It bridges the gap between historical canons and today’s obsession with face filters, illustrating how photography both produces and liberates our images. Bringing together work by fifty-five artists, from Cindy Sherman to Zanele Muholi, the exhibition responds to a pressing need: recapturing the gaze.

The power of the lens

The first section explores the origins of beauty, from antiquity to the 1960s and 1970s. In the latter decades, feminist movements rebelled against beauty ideals carved into Greek marble as an eternal punishment. The standards inherited by the West from ancient Greece were perpetuated through decades of ‘soft’ propaganda: magazines, advertising, Hollywood films and, today, the algorithms that feed on our insecurities.

Nowadays, an entire industry underpins beauty ideals. Tsilibaris puts it bluntly: “The industry that promotes numerous invasive and non-invasive aesthetic practices is a global economic driver. The exhibition reveals how this sector uses the power of advertising to echo and reinforce beauty stereotypes around gender, class and ethnic origin.”

Photography plays a central role in the exhibition’s contemplation of beauty. Can the medium truly escape its own logic of aestheticization, or does it simply perpetuate it endlessly? The curator seeks to nuance this apparent paradox: “I don’t think photography needs to turn against itself in order to look critically at physical beauty. Aestheticization is highly subjective. It is related to how the artist constructs the photograph, what they want to say, the artistic styles of the moment, and how works are experienced by individual viewers.” In doing so, Tsilibaris shifts the focus to curatorial intention and to the dialogue between artwork, artist and audience.

And this is where Picture Perfect takes an important leap: the critique becomes urgent. The context has changed. Who could have imagined, five years ago, that aesthetic procedures would become so widespread after COVID? Online meetings have confronted us with our own unflattering, pale, commented-on faces. Picture Perfect asserts that beauty is not an object to be archived.

Decentralizing the gaze

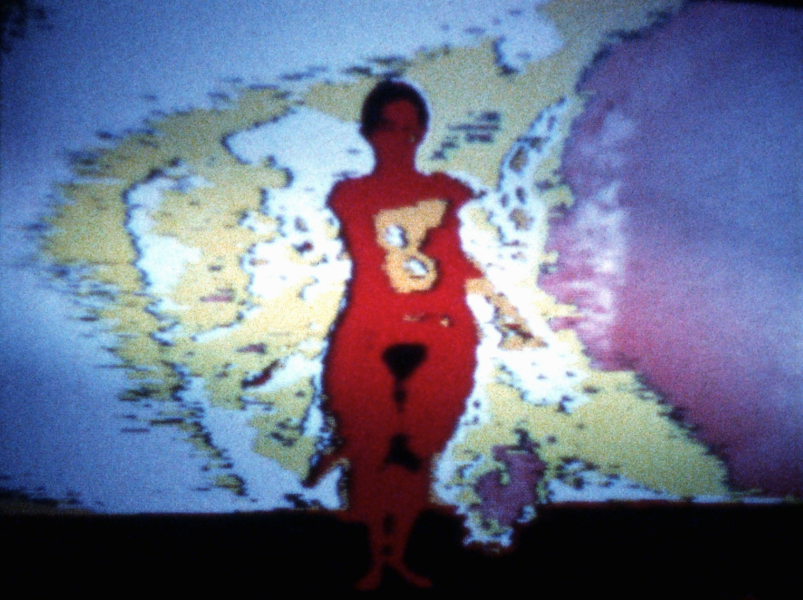

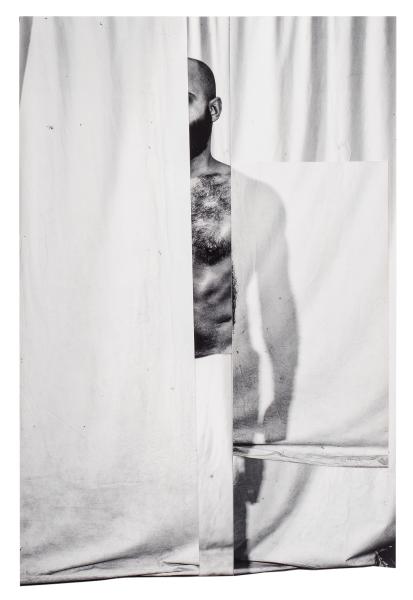

The project’s ambition is best reflected in the selection of fifty-five artists from diverse geographical contexts: from Congo to Afghanistan, from Japan to Norway. While this could be dismissed as convenient cosmopolitanism, decentralization is a deliberate choice. Canonical figures such as Cindy Sherman, Pipilotti Rist and Martha Rosler are represented, but they are joined by artists from other parts of the world whose work explores the global dominance of Western beauty ideals. Cindy Sherman embodies the moment when photography abandoned its pursuit of transparency. In a related vein, Pipilotti Rist transformed the screen into a physical interface. Martha Rosler examines the beauty standards society imposes on women. Together, the selection recognizes humanity in all its magnificent diversity, and in the ambiguities of bodies, genders and cultures. Western beauty is not only criticized but also decolonized through works by Yuki Kihara, Frida Orupabo and Zanele Muholi, who articulate its intersectional implications: beauty oppresses black, female and queer bodies most of all.

Aesthetic resistance

One of the most fascinating aspects of the exhibition is that it presents a complete genealogy of aesthetic resistance. Eleanor Antin, who took to the barricades in the 1970s. Hannah Wilke, who used her body as a weapon of critique. Ana Mendieta, who transformed performance art into a silent cry. The exhibition rejects linear chronology; its structure embraces the complexity and dialogue of multiple temporalities. This view of beauty functions as a kind of magnifying glass that both reveals and examines. It prompts us to consider how seemingly innocent criteria ultimately trap us in self-concern, in the restless inspection of detail – sometimes even to the point of discomfort. This resonates with the subtle words of the authoritative African American voice of Toni Morrison, author of Beloved: “Beauty was not simply something to behold; it was something one could do.” Picture Perfect demonstrates a rigorous approach at Bozar. The fifty-five artists do not seek to please. They liberate what images have suffocated. You will recognize your own reflection. The exhibition draws a line. You decide what you look at.