Under what circumstances did you arrive in Belgium?

I was born in 1981, in the middle of the Iran-Iraq War. It was two years after the Islamic Revolution. My parents, who were not at all political activists, decided to leave the country when I was four years old because they wanted to lead a normal life. However, they continued to maintain contact with Iran. I always say that we left Iran physically, but not mentally because, at home we ate Persian food, we listened to Iranian music, we were lulled by the poetry my father read.

Why with Salaam Isfahan did you decide to film Iranians during the 2009 Presidential elections?

The initial project involved capturing images of passers-by on the street using a very precise photo-cinema device because photography enables you to stop time and create moments of silence which, paradoxically, often reveal a great many things. In 2009, when I went to shoot the film, I realised that the Presidential elections were almost upon us. But they had taken a most unusual turn. The popular uprising sparked by the re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as President of the Islamic Republic had been preceded by a large popular movement: Iranians had already taken to the streets to call on people to vote for the other candidate, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, at the time supported by Reformers. When Ahmadinejad "won" despite the majority of Iranians having voted for his opponent, people revolted. In the film, for example, I ask two young people on bikes where they are going, and they say, "We're going to get beaten up." People were desperate, this election which they believed had been rigged was the straw that broke the camel's back and a deep sense of injustice was hatched, in actual fact, this discontent had already been smouldering for a long time.

What was the state of Iranian civil society at that time?

I found a society which was extremely informed, with people who, despite the regime, searched for information and were hungry for culture. For example, some of Pasolini's films which I watched as a student at La Cambre were screened secretly in the cellars of houses. There was a strong desire for life even if life had become more dangerous. I was able to see the major role that culture played in helping them resist despite the political situation. However, at the same time, I wonder if people were not resigned to accepting the current regime, developing a parallel, clandestine world, limited to the space of their own secret garden, in order to be able to tolerate their daily life. The trauma of the revolution and the Iran-Iraq War is still very present and I doubt that Iranians are ready to go through something so violent again. The war helped consolidate the regime because Iranians could not, at the same time, deal with the war and become involved in political resistance.

How did the I for Iran project come about?

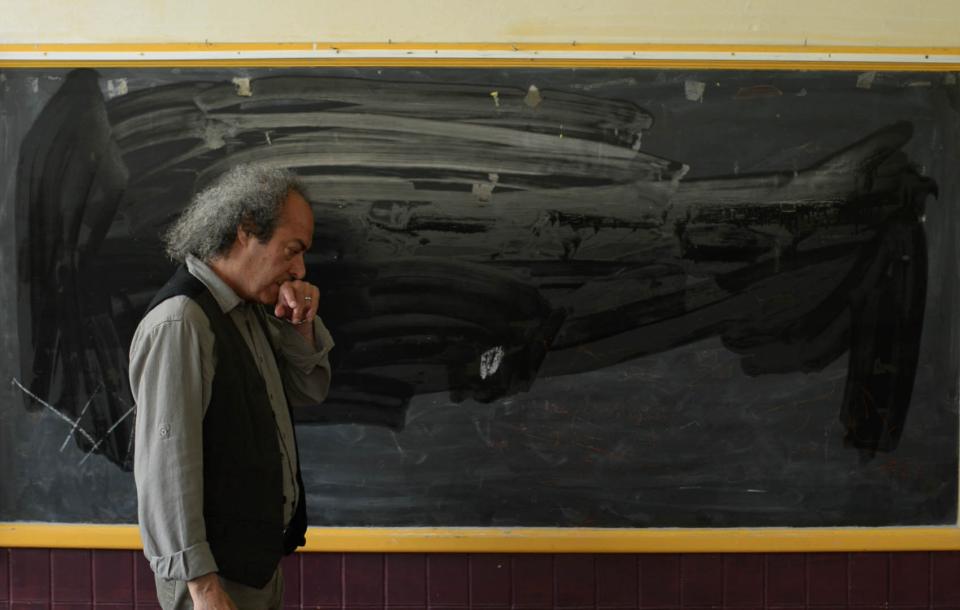

Originally, I just wanted to take Persian classes. From the very first lessons, I realised that basic words also had a political resonance and that, as a result, the language had lost its innocence. This is where the idea for the film came from: to film this learning process during which each word would also allow me to infer a small part of the story of modern Iran. I entrusted the role of teacher to Behrouz Majidi whom I had met through a mutual friend. I had already met many teachers for the film but I needed someone who was both a good teacher and a good storyteller. Behrouz combined these two qualities because he was an Iranian citizen who had fled his country and, therefore, had a very rich and dense history with Iran. I asked him to teach me how to write, a little like a primer, each time choosing a word with a different letter and linking it to a story presenting an extract from his life or his view on Iran. For me, it was essential to structure the teaching of the language around the country's recent history, and more specifically the Revolution, which is precisely the last lesson in a first grade Iranian child's language learning manual. And with Behrouz, the word "Revolution" was addressed by a man who had made it happen.

How did you position yourself in relation to your subject? As an Iranian or as a Westerner? Or both?

I think it was Cézanne who said "I don't paint the tree but the distance between the tree and me." This is well suited to how I position myself in relation to Iran in my films. For example, the collages I make in I for Iran have something very Belgian about them. It's a little like the offbeat look represented by Magritte in his painting The treachery of images, captioned by the famous sentence "This is not a pipe". As for Salaam Isfahan, it is clearly a film about returning home which Iranians living in Iran would probably not have been able to make. My films are always at the meeting point between documentary and fiction and offer a view of reality which highlights this point. More recently, I shot Faites sortir les figurants (Backstage Action) making the extras the main characters of my film, even though they are meant to remain in the background and only appear briefly. I found it interesting to reverse this approach and go to different shoots to draw attention to those who usually remain in the background. This inversion is not meant to be about cinema but rather about the state of the world and the way people are depicted in films. The extras are to image what people are to society, which treats them as the cinema treats extras.

In the presence of the Director Sanaz Azari and the Iranian film critic Bamchade Pourvali

In the framework of the EU HerMap Iran – Cultural Heritage Management Project