Her most famous film is undoubtedly Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, which the young Akerman (only 25!) made with a largely female crew. In painstaking detail, the film documents three days in the life of a widow who resides at – you guessed it – the Quai du commerce 23 in Brussels. For over three hours we follow a housewife (played by the iconic French actress Delphine Seyrig) as she tidies the flat, peels potatoes, cooks dinner, polishes her son’s shoes, runs errands, and prostitutes herself every afternoon. The repetitive rituals of daily routine build a feeling of dread that turns the slow-moving film into a mesmerizing thriller. It has only grown in stature since its release in 1975, and not just in Belgium and France: recently it has cropped up in several prestigious best of lists, especially in the UK and US, where it has achieved cult status.

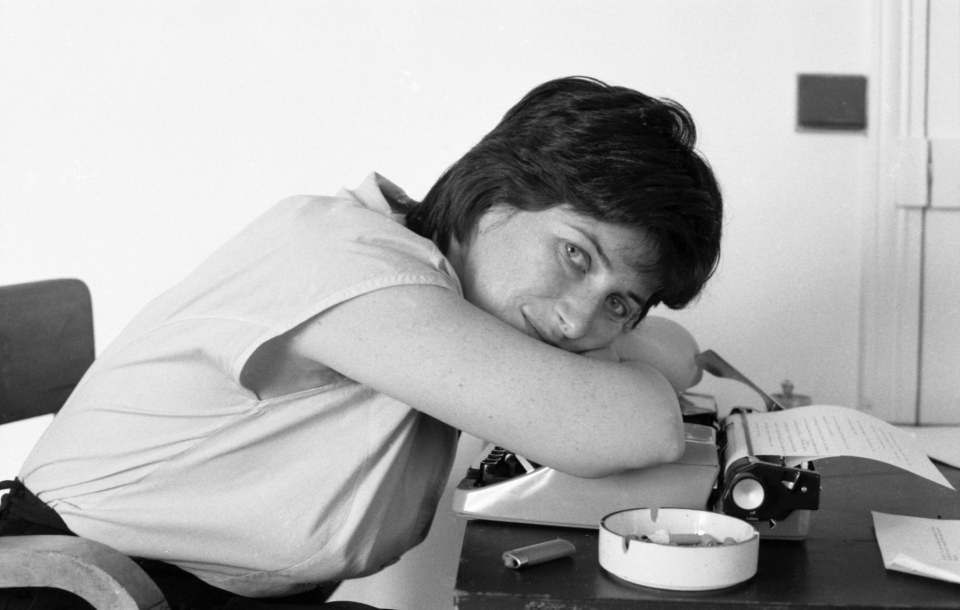

Before Jeanne, Akerman (born in 1950) had immersed herself in the underground film world of New York, where she arrived in 1971. It was a formative period that helped liberate her from the constraints of traditional film making. She filmed the run-down hotel and her fellow residents, and shot the streets of New York, juxtaposed with the letters sent by her mother from the Belgian home front. Her films were always deeply personal, and her mother Nelly, a holocaust survivor and her inspiration, always loomed large.

'Often when people come out of a good film, they would say that time flew without them noticing. What I want is to make people feel the passing of time. So I don't take two hours from their lives, they experience them.'

Akerman never conformed and made exactly the movies she wanted to make: fiction, documentary, experimental or essay films. She also made video and installation art and published a play and two novels of ‘auto-fiction’. This highly eclectic practice made it difficult to pigeonhole Akerman as the classic ‘film auteur’, which explains her marginal position in the film world. But from very early on she was also embraced and worshipped by many cinephiles, visual artists and other filmmakers, who saw her as an innovative radical and a pioneer of modern feminist cinema.

A more mainstream project was A Couch in New York (1996), an awkward comedy about psychoanalysis with Juliette Binoche and William Hurt. Akerman and her camera loved cities: Brussels, Paris, New York. But she travelled all over the world for her documentary work: to the American South, the Mexican border, Eastern Europe, or Israel. Her documentary films are not journalistic, but artistic and immersive. They rarely rely on narration or interviews, but are filled with portraits of people and of landscapes. There are some sober literary adaptations among her fiction films too: Marcel Proust, or Joseph Conrad, filmed in the jungle of Cambodia.

'Paris has too much culture; that culture is over your shoulders like a big, heavy weight. Here [in Brussels] it’s freer, because although there is a Belgian culture, it’s not recognized as a big culture. So, in fact, it’s like Czechoslovakia for Kafka. It’s a good place to work.'

Her last film was one of her most personal: No Home Movie (2015), a video portrait of her mother during her last days. The same year Chantal Akerman took her own life and, on her death, tributes by directors such as Claire Denis, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, or Gus Van Sant testified to her influence on contemporary film making. Todd Haynes said that watching her films was 'one of those experiences that change your way of thinking, of seeing, of imagining cinema'.