Bellezza e Bruttezza. Beauty and Ugliness in the Renaissance brings together precious works from Italy and Northern Europe by Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach, and Quinten and Jan Massys.

Bellezza e Bruttezza takes us back to a turning point in (art) history: the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, or the transition from the Middle Ages to the Modern era. The Renaissance breathed new life into the ideas and ideals of Greco-Roman Antiquity, inaugurating an age of discovery and scientific inquiry. The proportions of the human body were studied in unprecedented depth. Painters and sculptors gave form to beauty through mythological figures. Thus, at the entrance to the exhibition, visitors encounter the Three Graces and multiple representations of Venus, the goddess of love and beauty. Beauty appears as something divine and unattainable in earthly existence, reflected in imaginary figures enhanced according to mathematical models. One might speak of an assemblage of body parts - a precursor to today’s digital manipulation of images.

Botticelli’s Muse and the Hairy Girl

Muses do not exist solely in the divine realm. During the Renaissance, painters and sculptors also drew inspiration from living models. For his Allegorical Portrait of a Woman (c. 1475–85), Sandro Botticelli most likely had Simonetta Vespucci in mind, a Genoese noblewoman renowned in her time as one of the most beautiful women in Florence. Her beauty did not escape the attention of Florentine painters such as Botticelli himself and Piero di Cosimo. Simonetta did indeed pose for Botticelli, but after her death at around the age of twenty-three, she became what Beatrice was to the poet Dante Alighieri and Laura to Petrarch: an unattainable muse. Her wavy golden hair, dreamy gaze, upturned nose, full, softly curved lips and pale complexion recur in many of Botticelli’s female figures. Simonetta thus appears posthumously in what is perhaps the most famous portrait of the goddess of beauty: The Birth of Venus. She no longer posed as herself; she had become an allegory of beauty, an ideal image. According to tradition, Botticelli was buried “at the feet” of his muse in the Church of Ognissanti.

At the royal courts of Northern Europe, other unconventional models attracted attention: dwarfs, jesters, and the family of Pedro Gonzales, the hairy man from Tenerife. Gonzales suffered from excessive hair growth over his entire body - universal hypertrichosis - a genetic anomaly he passed on to his three daughters and his son. For Bellezza e Bruttezza, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna has lent the life-size portrait of Madeleine Gonzales (c. 1580). At the age of seven, dressed in a sumptuous gown, she was presented at the court of Duke Wilhelm V of Bavaria as a curiosity.

According to research conducted by Merry Wiesner-Hanks in The Marvelous Hairy Girls: The Gonzales Sisters and Their World, Madeleine and her sisters were not perceived by their contemporaries as “normal” individuals with unusual hair growth. Rather, they were regarded as hybrid beings, close to animality, and even assimilated to a so-called wild people believed to inhabit lands far from Europe or beyond the ocean.

Monstrous Faces

Artists were free to manipulate both beauty and ugliness. In his Treatise on Painting, Leonardo da Vinci emphasizes the power and freedom of the painter: “If the painter wishes to see beauties that inflame him with love, he is master of their creation; and if he wishes to see monstrosities that inspire fear, or things that are laughable and amusing, or truly pitiable, he is their master and their god.” Bodies were studied according to ideal proportions, but also deliberately distorted. In The Four Books on Human Proportion (1528), Albrecht Dürer produced anatomical drawings exploring all manner of bodily proportions of men, women and children, thereby achieving different sizes and types. Equally influential were Leonardo da Vinci’s Visi mostruosi - literally “monstrous faces”. With his own eyes, he observed the “deformities” of nature in hospitals and morgues. Yet in his Teste caricate (“caricature heads”), he also exaggerated the four main parts of the human face: the forehead, nose, mouth and chin. Was da Vinci seeking ultimate ugliness, the opposite of his work on ideal anatomical proportions in the Vitruvian Man, geometrically constructed from a circle and a square?

Da Vinci thus opened a path that, centuries later, would lead to press caricatures, satirical portraits in Montmartre, and drawings in which one may freely laugh at one’s own face or that of celebrities-a concept that did not yet exist in his time. During the Renaissance, under the influence of Antiquity and especially Plato’s theory of ideas, a strong association prevailed between beauty, harmony, superiority and goodness on the one hand, and ugliness, disorder, inferiority and evil on the other. The latter category openly invited laughter.

Youth and Old Age

We all experience it: beauty and ugliness are not distributed equally. In itself, beauty is not linked to social class. However, those with sufficient (financial) means can subsequently make themselves “more beautiful”. In the sixteenth century, manuals described the ideal female appearance: blonde hair, dark eyes, fair skin, rosy cheeks, red lips, a small nose, fine arched eyebrows, a high forehead, delicate hands, small firm breasts, broad shoulders and a rounded belly. This ideal is also reflected in painting and sculpture. Women used cosmetic recipes that were often toxic and dangerous in order to conform to these standards. They were Botox-like treatments before their time. The lower social classes had no access to such “cosmetic” treatments, either on their own bodies or through painters’ representations.

Moralizing and satirical scenes associated ugliness with the deadly sins, notably pride, avarice, gluttony and lust. Besides the lower classes, the elderly were also singled out. Everything had its season, it was thought. Making love at an advanced age was no longer acceptable; it was considered unnatural. Jan Massys ridicules an elderly couple in love through grotesque sexual symbols. A musician plays a half-deflated bagpipe, a pitiful phallic symbol. The old woman holds a jug, symbolizing the female sex. Behind her, a grimacing figure makes mocking comments and points to an empty jug.

The association of youth and old age lent itself to comedy and satire. Lucas Cranach painted around forty “unequal lovers”. Only three times did he pair an elderly woman with a young man. Bozar succeeded in securing one of these double portraits (c. 1520–22) for Bellezza e Bruttezza. This work has no emancipatory intent whatsoever. Generally, it is the young woman who seeks to lay hands on the elderly man’s purse. Here, however, it is the old woman who takes the initiative, smiling as she offers her money to a young man. Three teeth still protrude from her gaping mouth. Cranach mocks female sexual desire and warns the young man.

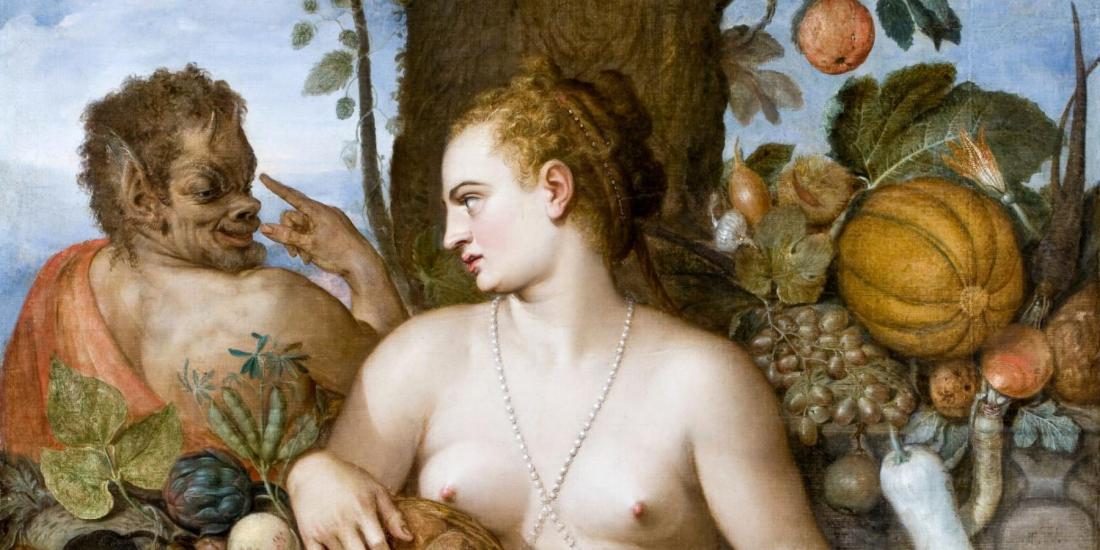

With Pomona (1565) by Frans Floris de Vriendt -the painting featured on the exhibition poster- we conclude our journey through beauty and ugliness where the exhibition began: in mythology. The scene is drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. A lover attempts to attract the attention of Pomona, who cares little for him, preferring the fruits of her garden and orchard. Her indifference makes her even more desirable in the eyes of numerous suitors. De Vriendt depicts her in the company of the satyr Pan, God of wild nature. His dark, animal-like appearance contrasts with Pomona’s bare, pale breast. It is ultimately Vertumnus, God of the seasons, who succeeds in seducing Pomona after a series of metamorphoses-by taking on the appearance of an old woman.