Few symbols are as powerful in their simplicity as the cross. It is probably best known as a Christian symbol, where it is linked to the crucifixion of Christ. In essence, though, the cross is nothing more than the meeting of two lines: the intersection between the horizontal and the vertical, the convergence of opposites. The spatial dimension of the cross is also found in many pieces of music, in the form of criss-crosses, reflections and reversals. The cross as both a symbol and a construction technique: that might be the shortest possible summary of Sofia Gubaidulina’s In Croce.

Sofia Gubaidulina and the art of connection

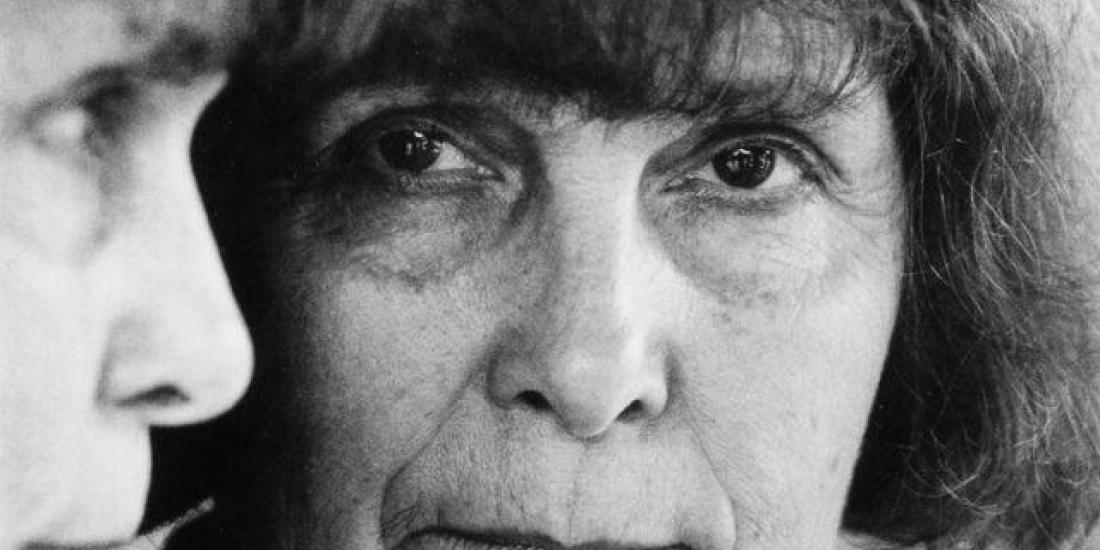

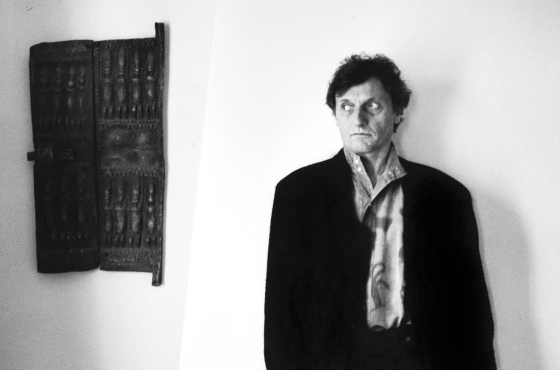

Sofia Gubaidulina (1931-2025) is one of the most famous Russian composers in the world today. Things haven’t always been that way, because like many of her compatriots, she was forced to conform to the political authorities or choose emigration. Between 1964 and 1989, her music for films and documentaries provided a stable income. However, she developed her personal musical language mainly in (and in dialogue with) the West. Thanks to a few European advocates of her music (including Gidon Kremer and Reinbert de Leeuw), she rose to international fame. In 1991, she moved to Germany, where she lived until her death on 13 March 2025.

Because her father had sworn against his own father’s religious fanaticism, there was no place for religion in the Gubaidulins’ home. That was also in line with Lenin and Stalin’s politics: they viewed religion as suspicious and undesirable. However, Sofia Gubaidulina felt a strong call at the age of fifty. She developed a highly personal vision of religion that also permeated her music. Quite a few of her compositions have a religious title, such as Alleluja, De Profundis, Einfaches Gebet, Jauchzt vor Gott, and even a fully-fledged St John Passion.

For Gubaidulina, though, religion is more than liturgical observance. We should understand it literally: re-ligio or re-connection. It is the artist’s task to make connections in a world where our entire lives are fragmented. In musical terms, Gubaidulina believes that art and culture can help us live ‘legato’ in a ‘staccato’ world. For her, the essence of music is in the sound, which does not necessarily need to be sonorous. This sound has a mystical nature, and creating sounds is a religious act.

“What is religion, actually? For me, this concept is literally re-ligio – a ligature that connects the horizontal line of our life with the vertical line of our divine presence. Somebody who creates something, such as a poem, enters the vertical domain. Someone like that is capable, even if only a little, of perceiving what exists in that dimension.” (Interview met Aleksey Munipov, 2012)

In Croce

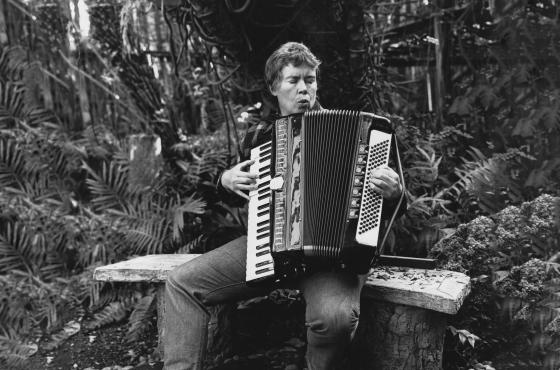

In Croce was originally written for cello and organ. The idea for this unusual combination came from Vladimir Tonkha, a cellist with whom Gubaidulina worked regularly. During the rehearsal, the composer saw how both musicians were doing their best to perform their own part, but something wasn’t right. She reacted with just two words, the title of the piece: In Croce. The musicians instantly understood what they were supposed to be doing. The essence of this composition is the intimate and yet impossible connection between the earthly cello (down in the church) and the celestial organ (high up on the rood screen). The metaphor of the cross makes this encounter possible. In 1992, thirteen years after she wrote the work, Gubaidulina adapted In Croce for the cello and bayan, a type of Russian accordion.

The form and progression of this composition are essentially very simple. The bayan begins in the high register and plays a descending line, as if the Holy Spirit were descending to Earth. In contrast, the cello starts in the depths and moves in generally ascending lines. At the end of the piece, the roles are reversed. The bayan wallows in deep clusters (low chords with many dissonances), whereas the sound of the cello has transcended itself and seems to have broken free from the instrument. Gubaidulina writes the cello part in harmonics here: high, fragile notes produced by putting very gentle pressure on the string with the left hand. The melodies played by the bayan at the beginning of In Croce are reproduced exactly by the cello, and the cello’s music finds its way to the bayan. At the beginning of the piece, the bayan plays a solo, but at the end the cello continues for a while alone. Everything is perfectly in the shape of a cross.

Graphic score

In Croce starts off as a traditional score. After about seven pages, however, the notation changes drastically. The cello is still notated traditionally, but the notes in the bayan part give way to parallelograms and squiggles notated on the staves. The parallelograms stand for ascending and descending clusters, while the squiggles offer an approximation of the melodic progression. The performer may choose the notes, as long as the contours more or less follow the squiggly lines. This is an example of ‘graphic musical notation’, where the performer has greater freedom.

Music as a power that elevates

In this work, Gubaidulina makes her standpoint as a composer succinctly clear. It is music – and, by extension, all the arts – that help us mortal humans to come into contact with the divine. We shouldn’t seek the divine in a god outside ourselves, but in the (mathematically explainable) mysteries of the cosmos and the depths of our own subconscious. The latter also reflects her interest in improvisation, a way of making music that she often used herself. In Gubaidulina’s view, music is crucial to ascend to a higher spiritual level. Music provides an extra dimension in our lives.