Hearing is one thing, listening is another. And “deep listening”? That can take many forms and intensities, but as far as Pauline Oliveros is concerned, deep listening is the most important thing. In music, in the experience of art, yes, even in life.

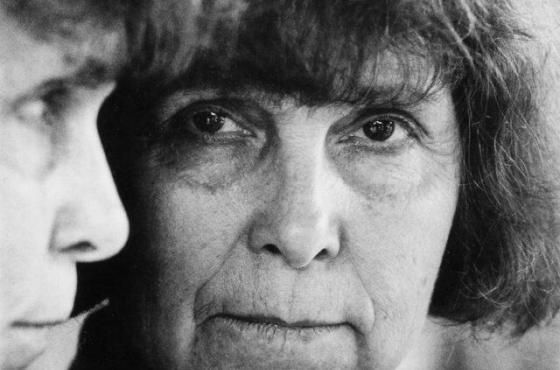

Pauline Oliveros

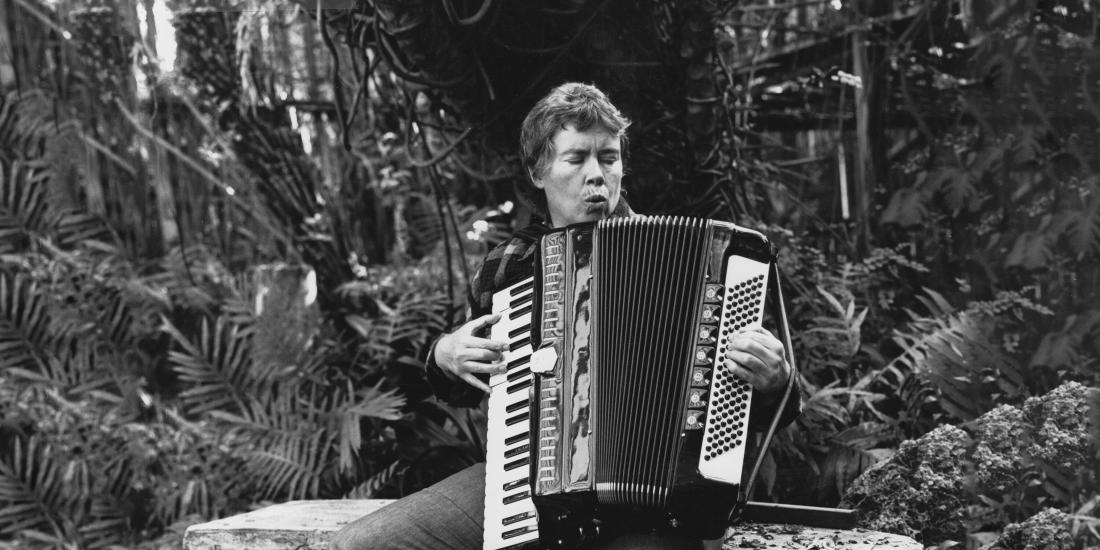

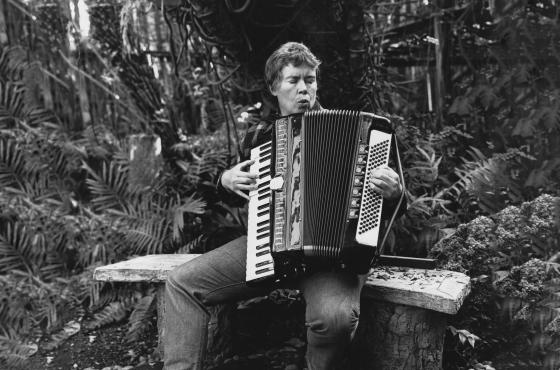

Pauline Oliveros (1932-1916) grew up in Houston, Texas, in a musical family; both her mother and grandmother were piano teachers. She would not continue that tradition, however, as she chose accordion and preferred noise to classical concerts. In her thirties, she collaborated with Steve Reich and Terry Riley, icons of minimal music. She was also fascinated by the possibilities of electronic music and worked on the San Francisco Tape Music Center. After heading the University of California's Center for Music Experiment in the 1970s, she founded her own foundation, The Pauline Oliveros Foundation in 1985 . There, she brought together her various interests, including meditation, into the practice of Deep Listening. With her Deep Listening Band, she also put her musical and aesthetic ideals into practice, with performances and recordings.

Deep Listening

For Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening was not just an activity or a temporary listening posture. She considered it a lifelong practice:

“The more I listen the more I learn to listen. Deep Listening involves going below the surface of what is heard, expanding to the whole field of sound while finding focus. This is the way to connect with the acoustic environment, all that inhabits it, and all that there is.”

In Deep Listening, we explore the distinction between natural, unconscious “hearing” and purposeful, conscious “listening”. To maximise the focus on active listening, body awareness, sonorous meditation, and interactive performance are combined. In addition, in developing such a listening attitude, Oliveros aimed for a deeper attention to everyday sounds, the sound of nature, and the awareness of thoughts, imagination and dreams. All this should contribute to a heightened awareness of the sonorous environment, a great sensitivity to sound in its broadest and at the same time deepest sense: the sound vibrations that surround us, but also the vibrations deep inside us.

“Deep Listening is exploring the relationships among any and all sounds whether natural or technological, intended or unintended, real, remembered or imaginary. Thought is included.”

A key experience in Oliveros' development of Deep Listening was an experimental performance in an underground water tank with a reverberation time of 45 seconds. The isolation and seclusion of this space, and the fact that even the smallest sounds had such resonance, did force Pauline Oliveros and her fellow musicians to make music differently, to listen differently.

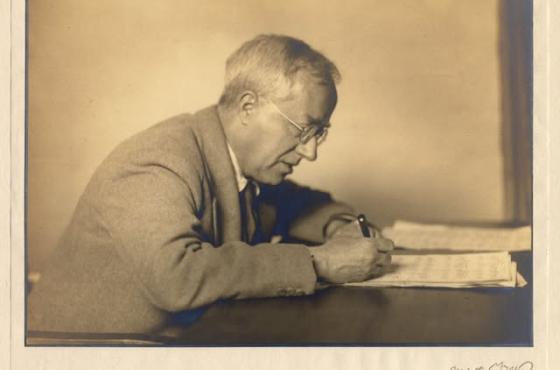

The focus on sound and noise, and not limiting music to the classical notion of a work or a score are reminiscent of the philosophy of John Cage. He too sought out experimentation and created contexts in which an aestheticising attention was turned to everyday sounds or chance circumstances, with the iconic 4'33 " as the most famous and perhaps most radical example. And Cage's aspect of meditation and link with Zen Buddhism is also very much present. Oliveros also inspired Cage's thinking: "Through Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening I finally know what harmony is. . . . It's about the pleasure of making music."

Political/ethical dimension

The classical musician-audience relationship is decentralised in Deep Listening. Performances of Pauline Oliveros' music or concepts are often collective events, experiences that arise “in the moment” and are shared by the performers and listeners present. In this sense, Oliveros is not a classical composer, and her oeuvre is not a list of compositions. She sums it up perfectly herself: "I never tried to build a career. I only tried to build a community". This sense of community building and connection runs like a thread through her work and also makes her a strongly socially engaged artist. She fought for equal rights as a convinced feminist, always stood up for people from the LGBTQ community (of which she herself was a part) and later in her career developed electronic tools and resources for people with physical disabilities. Inclusion is inherent in Pauline Oliveros' philosophy: ‘Deep Listening is a birthright for all humans.’ The focus on the sounds that surround us also quickly sparked an ecological reflex that fits perfectly within Deep Listening's aesthetic-philosophical frame of mind .

Earth Ears

Earth Ears is a so-called instructional score. With textual indications, Oliveros creates a framework within which the performers are free to realise their own version of the score. The fact that the music itself is not laid down in a strict score also indicates that the experience is more important than the precise musical content. Earth Ears is therefore a Sonic Ritual, a ritual where you are a different person after the experience than before. In this performance (18 January), percussionists Alexandre Babel and Tom De Cock engage students from KASK and Conservatory of Brussels. The composition has a cyclical form in which each cycle consists of four parts: Pattern - Transition - Change - Transition. The instruction for Pattern is that each player invents a pattern and repeats it all the time. The Change sections allow players to modify their patterns. The Transition sections are there to gradually transition from one section to another. A performance lasts at least four and a half cycles, but can also be worked out (much) longer. Oliveros also instructs that musicians should preferably be arranged around the audience and may also move around during transitions.