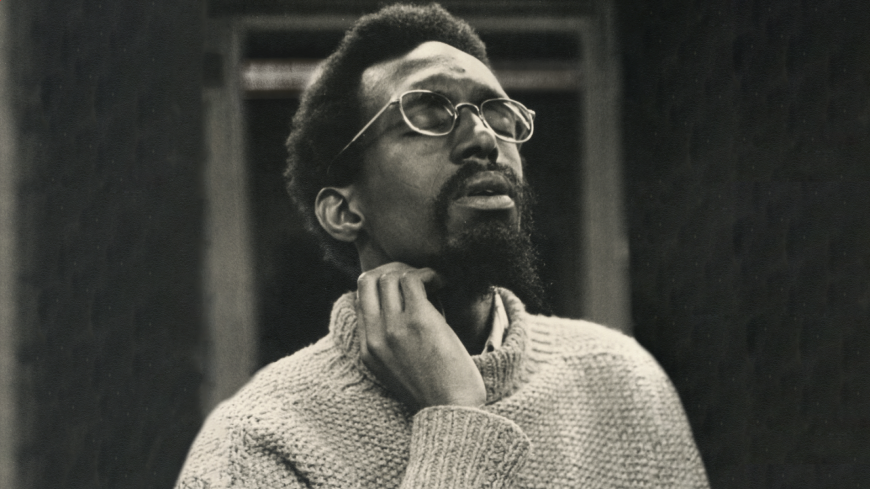

Eastman’s career initially developed favorably. Composer and conductor Lukas Foss recognized his talent and invited him to join a group of progressive composers at SUNY Buffalo, a creative hotbed where much of his early work was performed. There he met Petr Kotik, with whom he co-founded the S.E.M. Ensemble, which performed music by, among others, John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Pauline Oliveros. Eastman toured with the ensemble and was known as a gifted pianist and singer with a rich, expressive voice. As a performer he achieved success in Peter Maxwell Davies’s intense monodrama Eight Songs for a Mad King, and he collaborated with major figures such as Arthur Russell and Meredith Monk (he can be heard, for instance, on the iconic Dolmen Music).

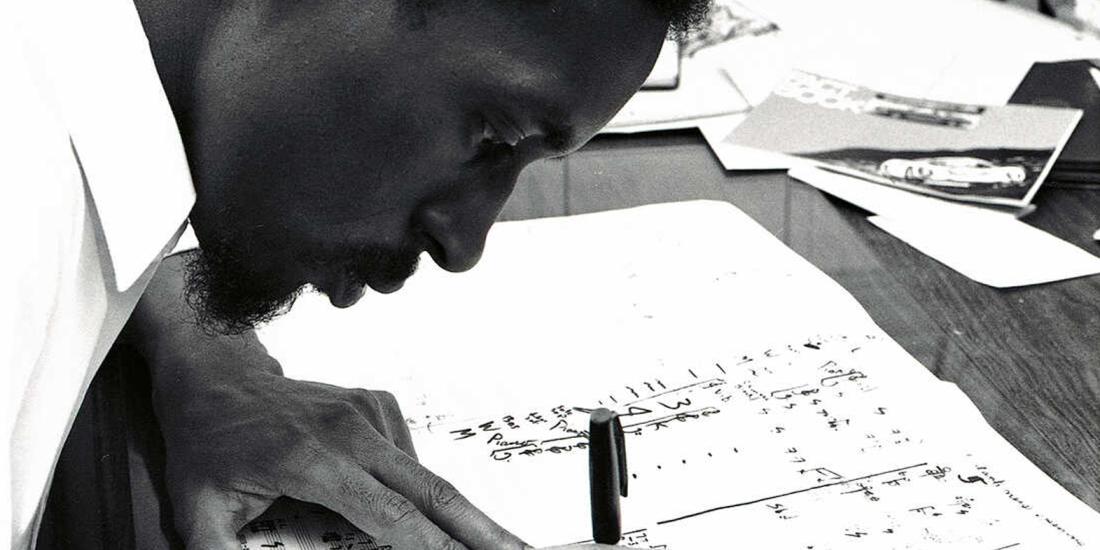

Meanwhile, Eastman composed music in a highly distinctive style. Whereas the earliest minimalist compositions by figures such as Reich and Glass often followed a strict process, Eastman worked without overly rigid rules. He built his music very gradually: by adding layer upon layer, he moved from a simple motif to a monumental sound. Each new layer contains not only the existing elements but also previously unused notes, rhythms, or harmonies. After a peak intensity is reached, the piece slowly disintegrates—a principle Eastman described as organic music. From the early 1970s onward, he also freely combined heterogeneous elements in his compositions. The joyful Stay On It (1973), for example, is based on a pop-like syncopated riff. Eastman repeats the motif endlessly, but gradually allows it to grind to a halt in dissonant and static passages, before it re-emerges with subtle harmonic changes. Thanks to this compelling mix, Eastman is regarded as one of the forerunners of postminimalism, a style that would only gain momentum a decade later. Long before composers such as Julia Wolfe embraced it in the 1990s, Eastman had already broken down the walls between uptown (the classical, academic scene) and downtown (the experimental circuit) New York.

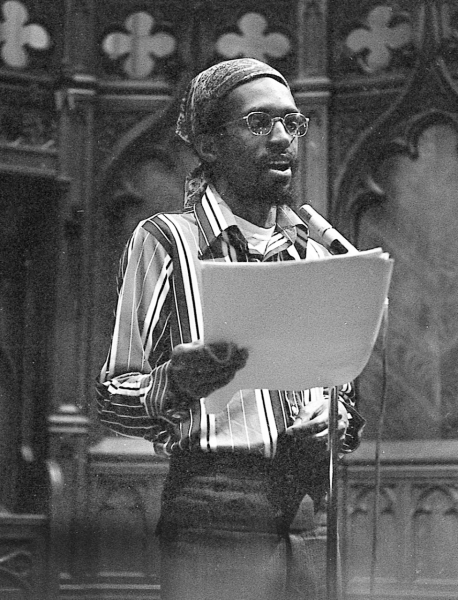

Eastman’s music possesses great vitality, an outspoken (emotional) directness, and a strong political charge in which his own identity becomes the stake: “What I am trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest—Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest.” With provocative titles such as Evil Nigger (1979), Gay Guerrilla (c. 1980), and Crazy Nigger (c. 1980), Eastman reclaims controversial terms and forces his audience to confront the political and social weight of his work.

In Gay Guerrilla, a piece with open instrumentation that is often performed on four pianos, he obsessively repeats a rhythmic figure (short–short–long) until a massive wall of sound emerges. In the middle of the piece, Eastman suddenly introduces a quotation from the Lutheran hymn Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. It is an intriguing choice: a hymn that urges steadfastness and carries connotations of struggle (“A mighty fortress is our God, a trusty shield and weapon”) becomes part of a powerful call for emancipation.

Eastman taught at SUNY Buffalo in the early 1970s but left the institution in 1975 after a controversial performance of a work by Cage. In the 1980s he became increasingly marginalized. He became homeless—during which time many of his scores were lost—and died in 1990 at the age of 49. The current revival of his work is due to his friend, the composer Mary Jane Leach, who began collecting and making available recordings and scores in the late 1990s.