When Gérard Grisey (1946–1998) conceived the idea for Le Noir de l’Étoile around 1980, he was looking at the same stars as Pythagoras, but through the lens of modern science and philosophy. About the harmony of the spheres he wrote:

“One should not conclude from this that I am a follower of the music of the spheres! There is no other music of the spheres than the inner music.”

Gérard Grisey and spectralism

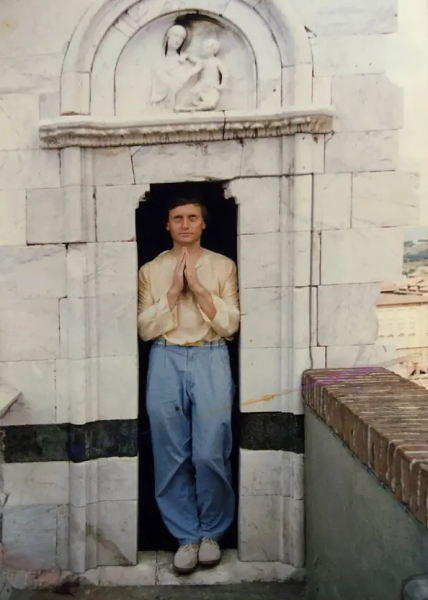

Grisey grew up in the turbulent years after the Second World War and began his musical journey as an exceptionally gifted accordionist. He also developed into a true intellectual, fascinated by a wide range of subjects, which is reflected in his compositions. At a young age he developed a strong sense of religion and saw composing as a way of giving shape to his belief in God. At 17 he wrote in his diary that, for him, God was rhythm—the pulse of life and love. He wanted that rhythm to play a central role in his music.

During his studies, and in particular through his contacts with Olivier Messiaen and Henri Dutilleux, he developed a musical language and technique aligned with his own era. He was critical of the rigidity of serialism and recognised the challenge facing music in the post-serial age: “New music seems to have lost all sensitivity. It appeals only to our intellect. The serial composer is more a scientist than a poet.”

His musical language evolved toward what we today call spectralism: music rooted in the physics of sound and the search for new timbres and sonic structures. Spectralism contains an inherent paradox that we also find in Grisey’s work (and particularly in Le Noir de l’Étoile). The complex relations between frequencies form an almost mathematical foundation, and many composers rely on extensive calculations to make musical decisions. At the same time, the quest for new sounds is highly sensory, aimed at the physical experience of sound. Spectral music also has a sensual side.

Despite his fascination with science, Grisey sought an art that was human—built not only on mathematical principles but also capable of moving the performer or listener. As a person, he was anything but a dry scientist. Biographies devote many pages to his interpersonal relationships, especially his views on love and sexuality. He married Jocelyn Simon in 1970, but monogamy did not suit him. Over the years his Catholic devotion had given way to other passions, which he pursued with equal spiritual fervour.

Le Noir de l’Étoile

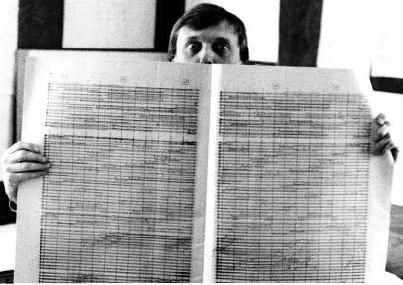

Grisey disliked the term spectralism because it overemphasised pitch and harmony. In 1979 he composed Tempus ex Machina for Les Percussions de Strasbourg, a work in which not a single pitch can be detected. This percussion piece focuses on rhythm and time, and would later be integrated into Le Noir de l’Étoile.

The inspiration for the work came while Grisey was a professor at the University of Berkeley in California in the mid-1980s. There he met Joe Silk, an astrophysicist who introduced him to the wondrous world of newly discovered pulsars. Pulsars are stars that rotate extremely rapidly and emit electromagnetic radiation. On Earth, these are perceived as fast, regular pulses. The idea that far out in the cosmos there is a pulse that reaches Earth after thousands of years naturally appealed to a composer like Grisey, who in his youth saw God as the rhythm of the world. Grisey later wrote that he was immediately “seduced” by the phenomenon and instantly thought—like Picasso when he found an old bicycle saddle—“what can I do with this?”

The premiere took place in the dilapidated Hallen van Schaarbeek on 15 March 1991, after a lengthy search and tough negotiations to secure the necessary funding, during which Grisey is said to have broken a chair in the heat of discussion.

Structure

The first part of Le Noir de l’Étoile consists of the accelerating and decelerating pulses from Tempus ex Machina. Grisey layers six different tempo strata on top of one another, just as a single fundamental pitch is built from the accumulation of various frequencies. During the final sounds of this first episode, we hear for the first time a sound from space: the Vela pulsar. From these cosmic vibrations a new instrumental episode emerges, once again featuring complex processes of tempo transformation. For Grisey, time is elastic, contrasting with the seemingly eternal regularity of the pulsar. After some time another pulsar appears in the electronics, sounding briefly on its own before the percussionists return. In the third and final instrumental passage, Grisey shifts the focus to metallic instruments, introducing an entirely new arsenal of sounds. The rhythm becomes highly irregular here and the complexity reaches its peak.

Performance at Bozar

Ictus Ensemble approaches this highly complex score with great attention to the spatial dimension of the work and its sensory impact. The first part is often performed with great force and energy, but in this version the musicians search instead for refined interplay and interaction between the different tempo layers. Here too we find an interesting paradox. The musicians play with a metronome (through earpieces) so that everything can be perfectly synchronised. Although this may seem mechanical and inhuman, this method ensures that Grisey’s carefully crafted temporal structure is precisely realised. In this way, the different layers of the music interact and the acoustic phenomena Grisey sought emerge. Mathematical precision gives rise to sensory enchantment.