As we speak, world events remind us of hatred, the inability to dialogue, and extreme violence... In short, the very opposite of what A little bit of the moon tackles: friendship and sharing.

The initial inspiration for the work stemmed from the Gaza and Lebanon conflicts following Hamas’s attack on Israel on 7 October 2023. It was a bleak starting point. What significance does friendship still hold in the face of such catastrophe? As we speak (19 June 2025), the situation continues, now extending to Iran. So, yes, our primary concern became the idea of friendship – how two people from different backgrounds can meet without one dominating the other. We sought common ground: music, poetry, and philosophical reflection. Then Anne Teresa introduced the concept of the ellipse, which became the foundation of our research.

Looking at the piece today, how well has this concept of ellipsis endured? The piece presents a conversation – a sensitive sharing of your practices as pathways towards understanding one another. How does the idea of ellipsis manifest?

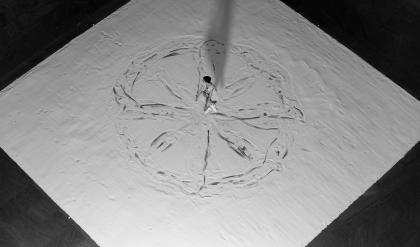

An ellipse has two centres, not one. This relationship is crucial: it signifies two people working together. The number twobecomes essential. One is unique, three represents many – both hold rich symbolism. In Arabic, for instance, two suggests a pair. With one, then two, you reach the threshold of many. The number two can either return to one or expand outward towards plurality.

Like a bridge, or a sort of hinge?

Exactly – a door to the many. In other terms, two lies between the ego and the community, the family, the bloc. It offers the possibility of maintaining one’s singularity without dissolving in the collective, while allowing a relationship with the many. We do not want to return to one: God is one, the dictator is one.

So when we return to the ellipse, it has two centres that work together. They may be close, but they never merge into one, nor multiply into three. The sum of the distances from any point on the curve to each of the two centres is always constant. It is a balance. In short: it is about collaboration. That concept carried us all the way to the Moon.

This idea of constant balance reflects how you share practices – and the curiosity you have for each other's work.

A simple definition of friendship is mutual support. While we questioned and discussed complex issues throughout, we were constantly offering things, and those offerings often became something else. Sometimes they merged. Again, the concept of ellipsis appears – or, if you will, A Little Bit of the Moon. Speaking of which: the moon never reveals the Earth its hidden half. From Earth, you can never see it, just as we can never fully see the other side of things – of people. We must find alternative ways of perceiving. This is like cinema: the counter-shot – how do you invent new ways of sensing the invisible through the visible?

Among the materials that influenced A Little Bit of the Moon was Violin Phase, a solo by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, first performed in 1982, and still part of her repertoire today.

This was the first work of Anne Teresa’s I saw, and it struck me profoundly – the way she approaches dance, rhythm, and movement. It certainly shaped our approach to ellipsis: varying dynamics, sometimes desynchronised, sometimes moving in harmony.

Music plays a central role in both your practices. How did you develop the musical language of A Little Bit of the Moon?

From the very start of our collaboration, music played a central role. Initially, it lacked a direct link to the piece. We shared a wide range of music, from classical to pop. Later, we explored songs about the moon: Nina Simone’s In the Evening by the Moonlight, Charles Trenet’s Le Soleil et la Lune...

And both of you perform music in the piece – though neither is a professional musician. That creates delicate moments, revealing something less polished and more human. Nearly a counterbalance to the concept of performance.

Absolutely – in that sense, we are revealing the vulnerability of being human. We live in a dichotomous world. Like in conflict, we are expected to choose a side – one or the other. But this relates back to the principle of the ellipse, and of the number two: it is not about binary opposition. There is not only love, nor only hate. The two are always in conversation. That is the role of number two – the units are metaphorically joined. They need each other. They offer something richer than mere duality.

Throughout this conversation, we have discussed real events as well as feelings and perceptions. Your work is often viewed through the lens of fiction and reality. Does this distinction still hold significance, especially here?

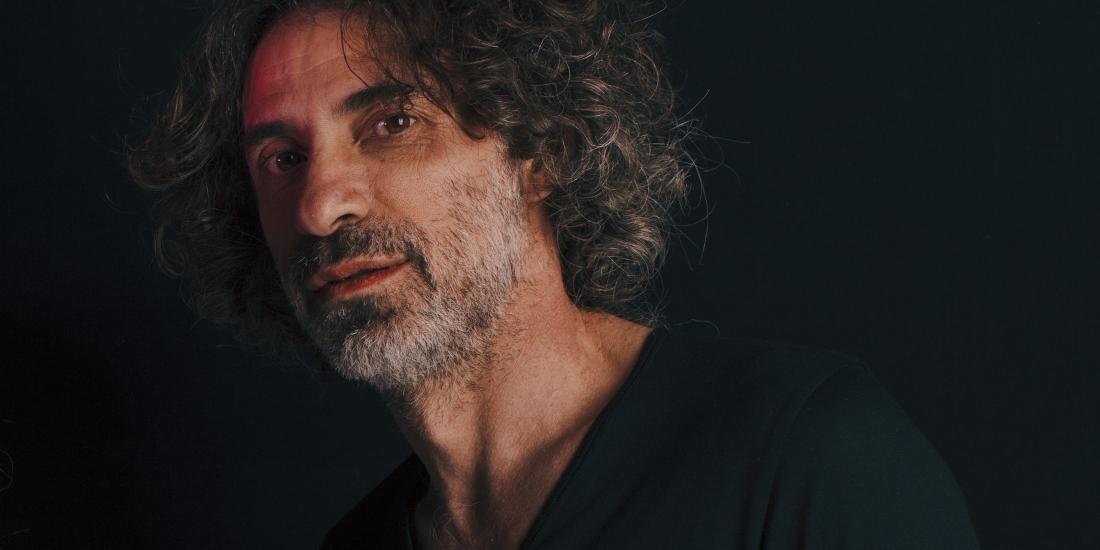

Everything is intertwined. The piece sits between the two, but it does not address that issue. Everything is quite clearly staged in this regard. There is nothing that prompts the audience to question it. The subject is straightforward: this kind of relationship – friendship. It is obvious to the audience. There is nothing particularly complex to analyse, politically or philosophically. It concerns an encounter between two individuals from different regions, backgrounds, and practices.

But still able to dialogue…

Fiction and reality were not really part of our discussions. Things emerged in layers. Perhaps because there is so little text – and when there is, it is in the form of stories. Movement offers far more freedom than language. It tends towards abstraction, and that abstraction allows the audience to imagine – to respond with their own contributions.