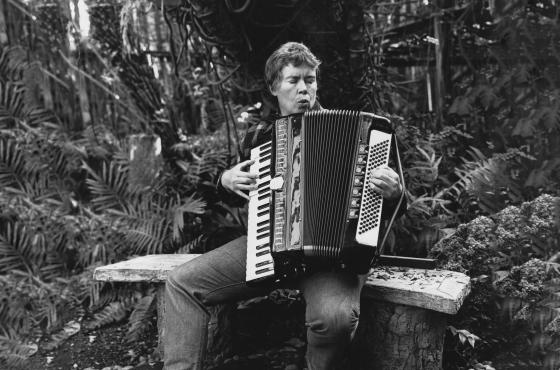

A birthday present to himself. That’s what Dmitri Shostakovich’s Second Cello Concerto was. As with the first concerto, which he had written seven years earlier, he had one of the most important soloists of the 20th century in mind: his good friend Mstislav Rostropovich (see image gallery). But that’s really all the two pieces have in common. The virtuosity and exuberance of the first concerto give way to a darker, more introspective atmosphere in the second. Where the first concerto is still fairly traditional in structure, the path taken in the second is more idiosyncratic. A slow first movement is followed by two fast movements that run into each other, rather than the more usual sequence of fast-slow-fast.

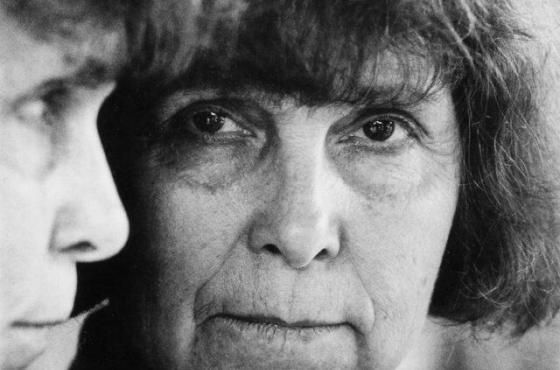

Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich’s biography has been written and rewritten many times. The aim hasn’t always been to present a clear picture of the composer’s life: sometimes it was a matter of fitting him into a political or ideological narrative. Officially, he was a hero of socialist realism, the composer who embodied Soviet ideals as an artist and a human being. Elsewhere, specifically beginning with Solomon Volkov’s biography in 1979, we read the story of someone who tried to express himself personally in every possible way, despite the strictures of authoritarianism; someone who even expressed criticism of the Communist regime. This gulf between artistic freedom and the need for government approval is a constant theme in his life. Besides the many official accolades he received, there were also conflicts and tensions. The best-known example is probably the opera Lady Macbeth (1934), which was banned by the Communist Party because the story was not moralistic enough.

Collaboration – or not – with Mravinsky

Even in 1962, the composer still came up against the limits of the politically acceptable. That was the year when his Symphony No. 13 for bass soloist and orchestra was premièred. The work is entirely based on poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, in which the thirty-year-old poet takes issue with the prevailing antisemitism. Despite the ‘Khrushchev thaw’, the period after Stalin’s death when censorship was a little less strict, Yevtushenko’s poems were still felt to be too critical. The symphony was not banned, but the government intimidated musicians to prevent them from playing it. The conductor Yevgeni Mravinsky, a loyal friend of Shostakovich, withdrew on the pretext that he did not want to conduct music with a choir and vocal soloists. The soloist, Boris Gmyirya, withdrew under pressure from the local branch of the Communist Party. After much wrangling, the première did go ahead, with Kirill Kondrashin on the conductor’s podium.

The whole situation caused a rupture between Shostakovich and Mravinsky and also soured the relationship between the conductor and Rostropovich. When Mravinsky backed out again in 1966, just two weeks before the première of the Second Cello Concerto (due to a lack of time, now), Rostropovich lost all faith in him and played the première with great enthusiasm under the conductor Yevgeni Svetlanov.

Birthday music

Shostakovich loved celebrating his birthday, preferably with new music. The Second Cello Concerto was one of the pieces he composed for his sixtieth birthday. On 27 April 1966, he wrote a letter from a sanatorium in the Crimea to his friend Isaac Glikman:

“I’ve just finished my second concerto for cello and orchestra. Since this piece doesn’t have a literary text or programme, I find it difficult to write about. It’s a grand affair, in three movements. The second and third movements are played with no break between them. In the second movement and the climax of the third, there’s a theme very similar to a famous song from Odessa: Kupite Bubliki (Buy Our Pretzels). […] As I was composing it, I naturally thought of the magnificent M. Rostropovich. I’m counting on him to perform the piece.”

The first performance, at a birthday concert on 25 September 1966, was also Shostakovich’s first public appearance after a heart attack earlier that year.

Symphony with soloist

This concerto is sometimes described as a symphony with a solo cello, because the score is less focused on the virtuoso display of the soloist, certainly in comparison to the first concerto. In fact, Shostakovich had initially intended the first movement, Largo, to be part of his fourteenth symphony. The music is based on a solo line in the cello that is gradually coloured by the cellos and double basses in the orchestra. What is striking is the interaction between the soloist and percussion. The xylophone creates a strange, almost ironic effect, especially in combination with the high woodwinds. The bass drum, in turn, is an unexpected voice in the cadenza.

As mentioned above, a folk tune appears in the middle of the concerto. Once again, it is the soloist who opens the debate and pulls the orchestra into a playful exploration of march rhythms, glissandi and caprioles. A fun detail for the analyst (or the very attentive listener) is that the same motif returns over and over again in different forms: sometimes faster, sometimes slower and sometimes even in different tempos at the same time. This says something about the way the composer ‘plays about’ with musical ideas and creates unity in this short middle section.

A first attempt at a closing movement ended up in the waste-paper basket, and the composer started again from scratch. The result is a lively finale, again with an unusual role for the percussion and a final nod to the folk tune from Odessa. Shostakovich lets the finale flow straight from the end of the second part, with the drum roll and fanfare motifs in the horns marking its start. Here, too, there is a special place for percussion. This time it is the tambourine that accompanies the cellist in the opening cadenza. What follows is a series of contrasting passages displaying every imaginable facet of the cello: lyrical, virtuoso, double-stopping, and at the end, a low D sustained for an extremely long time.

On 28 November at 7pm, Klaas Coulembier will give a bilingual (NL-FR) introduction to this iconic work. Location to be announced.