Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus, John Gray proclaimed in capital letters on the cover of his international bestseller in 1992. In fact, though, only the first half of the title was in capitals. Blue ones. The second half was in graceful, pink italics. So you didn’t have to look far to find the stereotypes. But whether or not you believe in categorical differences between men and women, it’s fascinating how people throughout history have associated the planets with human characteristics. This astrological approach – rather than the celestial bodies themselves – inspired the English composer Gustav Holst in 1914 to write an orchestral suite in seven movements, one for each planet (excluding the Earth) known at the time.

On holiday with friends

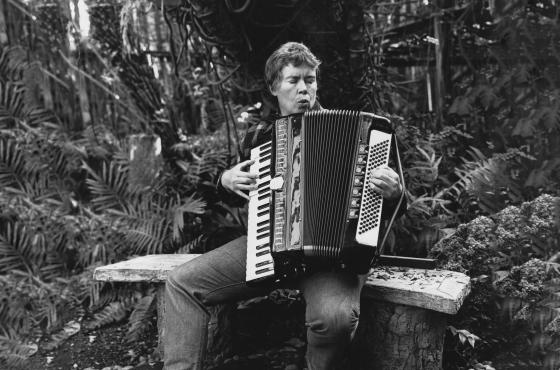

As a young man, Gustav Holst suffered from persistent neuritis in his right hand, leading him to give up his budding career as a concert pianist and opt for the trombone. He hoped that a wind instrument would also be good for his asthma, but the main benefit turned out to be that as a trombonist, he learned all the ins and outs of a symphonic orchestra.

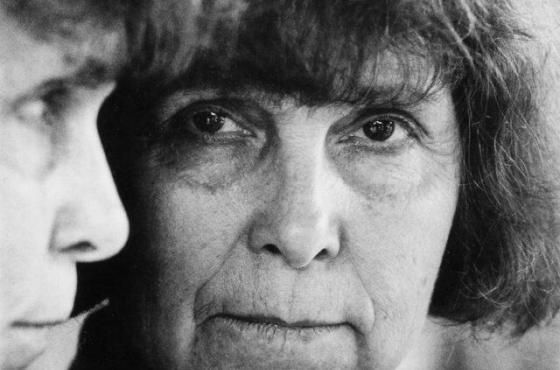

After working as a professional trombonist for a few years, Holst decided on a career in education in 1905. He lived modestly, with long hikes as his main leisure activity. He only travelled occasionally in his life, to Algeria in 1908 (where he visited the desert on a bicycle) and to Thessaloniki and Constantinople in 1918. While here was there, organising concerts for demobilised troops after the First World War, he felt it would be better to change his name from Gustavus Theodore von Holst (an inheritance from his German ancestors) to Gustav Holst.

A more important journey was his trip to Spain in 1913. Holst was depressed because his composing career wasn’t getting off the ground. To lighten his depression, Balfour Gardiner and the brothers Arnold and Clifford Bax invited him on holiday. Holst spent a lot of time in Spain exploring on his own, but when they were together, Clifford inspired him with stories about astrology. This is apparently how the orchestral suite Holst had in mind came to take the form of The Planets.

Not descriptions of planets

In a booklet that Holst regularly consulted, called What Is a Horoscope and How Is It Cast, Alan Leo explains how the position of the stars and planets at the time of someone’s birth influences their character. We should understand Holst’s music from that perspective. He is not trying to depict the planets in themselves, as Richard Strauss describes the Alps in An Alpine Symphony. In fact, Holst is not interested in space, but in the human psyche and how it can be explained. The planets are metaphors, or as he once put it in a lecture, “mood pictures”.

The working title of the orchestral suite was correspondingly abstract: Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra. Holst seems to be referring here to Arnold Schönberg’s Fünf Orchesterstücke, which he had heard in 1912: abstract compositions that shine with a wealth of orchestral colour. Holst’s manuscript already included the subtitles (the Bringer of War, the Bringer of Jollity, etc.) but he didn’t add the names of the planets until later. What the planets symbolise was more important than the planets themselves. For example Mars, the Bringer of War has nothing to do with the First World War (which only broke out after Holst had finished this movement). The music is more a reflection of the emotional and psychological state that we associate with war, or the belligerence in human nature that – depending on the position of the stars and planets – becomes more or less prominent.

Innovation and familiarity

This somewhat philosophical reading of The Planets doesn’t detract from the rich imagery to be found in many passages. It’s hard to miss the lively fluttering of Mercury, the winged messenger of the mythological gods, when woodwind and stringed instruments toss a whirling melody back and forth between them. Or the good-natured joy in Jupiter, the planet that stands for happiness and optimism. The middle section of Jupiter – that every Brit can sing along to as I Vow to Thee, My Country – expresses the grandeur of the biggest planet in the solar system. In Neptune, Holst adds a female choir to emphasise the mystical atmosphere. The link with Debussy’s Sirènes – a work that Holst would certainly have heard in 1909 – is more than clear, in both the sound and the content of the piece. Neptune is the god of the sea, where Debussy’s sirens live.

Maybe these layers of meaning are the reason that this composition brought Holst into the public eye at last. He also manages to balance innovation with familiarity. He uses tonal triads but places them alongside or even on top of each other in unconventional ways to create unusual dissonances. Each of the seven movements has a clear identity, with its own rhythms and melodies, but also its own orchestral colours and moods. In this way, the great orchestrator conveys astrological insights (how the celestial bodies keep each other in balance) in a musical logic that ascribes to age-old formulas of variation and unity. This is why The Planets is sometimes interpreted as a symphony in disguise. From that perspective, Mercury and Uranus act as the scherzo, with Venus representing the traditional slow movement. The focal point is Saturn, the enigmatic section that Holst himself was apparently very pleased with.

Success and after-effects

The Planets gave Holst the renown he had sought for so long, although he later resented that he was always associated with that one piece. What Holst could not have predicted was that the influence of The Planets would extend infinitely further than his own fame, especially on the big screen. Films about space often echo the sound universe that Holst created. John Williams might be considered the biggest amplifier of Holst’s musical fantasy. The music for Star Wars is full of quotations, and we also find musical references in other films. In the Harry Potter films, for example, the mail-delivering owl Hedwig has a theme related to the winged music of Mercury, even including the heavenly notes of the celesta.

On 21 November at 7pm, Klaas Coulembier will give a bilingual (FR-NL) introduction to this iconic work. Location to be announced.