Although their visions differ, Serra and Goya share a demanding visual approach and an obsession with texture and spontaneity. Their connection is not thematic but rather lies in a shared quest for a new, expressive language, free from convention and rooted in keen observation of reality. This connection is evident in Los Caprichos (The Caprices), as well as in Goya’s more courtly or Rococo works. A dialogue also begins with Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) and the Peintures Noires (Black Paintings). For Goya, beauty ceases to be an end in itself; art becomes a means to explore truth, marking a shift toward dark sublimity and a new way of expressing the world. In presenting his Caprichos, Goya developed a new visual language through a sequence of silent, reality-derived images. He aimed for art rooted in raw observation, capable of capturing the spirit of an era and, in a sense, breathing life into it. This vision, which prefigured cinema, explains why Spanish film awards bear his name.

Goya did not invent humanity’s beastly side, but he captured it in a quasi-photographic, cinematic way. Serra admires this instant composition, which showcases fleeting expressions — those subtle movements of face and body that hint at something more profound. Drawing inspiration from Los Caprichos (The Caprices), Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War), and Los Disparates (The Follies), he recognises the need to get very close to see what lies beyond first impressions: the value of textures, the almost animalised faces, the witches, the erotic gaze on women’s bodies — stripped of mythological attributes, more carnal, nearer to the unconscious, seeking ecstasy — something Buñuelian. He is also fascinated by Goya’s depiction of bullfighting as a circular spectator sport, with its almost playful cruelty and the resilience of life that persists even amidst suffering.

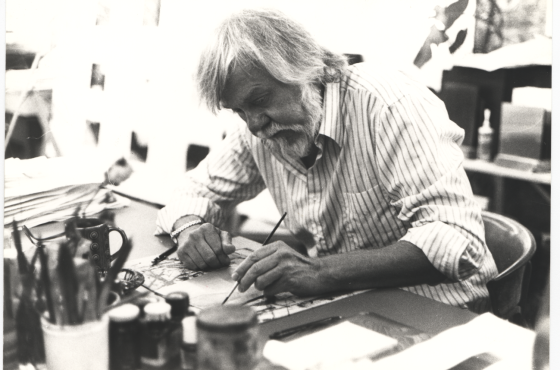

Serra appreciates how Goya, as a Spanish artist, portrayed a structural backwardness that has long been a characteristic of the country and remains evident today. In December, Albert Serra will be at Bozar to discuss his creative process and his cinematic interpretation of Goya. After studying comparative literature in Barcelona, he first gained recognition in 2006 with Honor de cavalleria (Honor of the Knights), revitalising Spanish cinema and establishing his unique style on the international stage. Over the past twenty years, he has worked across film, theatre, and gallery and museum spaces, participating in major events such as documenta in Kassel and the Venice Biennale. Having won the Golden Shell at San Sebastián in 2024 and the Golden Leopard at Locarno in 2013, he is a familiar figure at major festivals.

Trust Albert Serra

His characters are detached from society’s perceived centre, from ordinary life, norms, or reason. They belong only to themselves. Serra draws them from history, literature, current events, or with a nod to Fassbinder. They seem cursed by a nineteenth-century romantic fate: legendary figures, superior to humans because they have conquered death, yet also less human, exiled from time, longing to belong because they are denied it. Romantic and sceptical, myth-maker and relentlessly observant, Serra shuns the mediocrity of existence that still blindly trusts in progress — now revealed as an illusion — in the face of the world’s contradictory spectacle. He retains aesthetic control without confining himself to any preconceived form. Rather than following a script, he embraces the expressive potential of rigorously chosen faces, bodies, and spaces. Trusting the camera to capture both visual and temporal textures, he uses editing to construct a unique cinematic language. His freedom stems from producing his own films, which limits accountability and offers the audience space for contemplation. As a result, time in his works acquires a gravitational quality — it floats, drifts, and flows like a prayer.