John Baldessari (1931-2020) was raised in a world of colliding languages. His parents were immigrants to America, his mother from Denmark, his father an Italian-speaking Austrian citizen from Southern Tyrol. John himself, born in 1931, grew up in the paradoxically named small town of National City, California, just south of San Diego and twelve miles—nineteen kilometers—north of the Mexican border. Raised in a broken-English-speaking household, he would also have encountered Spanish throughout his youth.

Looking back on his upbringing, Baldessari wrote about the intersection of location and language as he experienced it in National City:

"I like to have a lot of books and magazines around that I can pick up and read. That’s sort of my surrogate world, along with TV. I think that comes from growing up in a ghetto where there weren’t any books or any rich life. I had to send away for books and magazines; I sort of imported my culture for myself. Both my parents were European immigrants . . . and there was no common language. I probably have more regard for language than I do for art specifically because I read more about language and writing than I do about art. . . . What propels me is that I see words and visual images as somewhat interchangeable. I don’t prioritize them; I play very much like an author or a writer. After working in art now since 1957, I’ve picked up some skills in orchestrating meaning."

Baldessari, like many of his peers in Conceptual art, considered language as a sculptural material that carried the same artistic weight as pictures, if not more. While artists including Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner removed “art signals” such as paint on canvas, expression, and visual imagery from their work, Baldessari sought an even balance between text and representation. In Goya’s etching portfolios Los caprichos (The Caprices, 1797–98) and the posthumously published Los desastres de la guerra (The Disasters of War, 1810–20) he recognized a template for how images and text could balance on intellectual and visual planes, and yet, when unified, construct new, congruous meaning.

In 1926, the San Diego Museum of Art was bequeathed a few loose plates from Los caprichos, including Tu que no puedes (You Who Cannot), which Baldessari recalled seeing several times on school trips and later when visiting the museum as a young adult. Like others in the group, Tu que no puedes fuses a politically loaded image with underneath it a short, barbed text, which serves as the etching’s title. The script adds a layer of context to the image—a depiction of two exhausted peasants carrying on their backs two seemingly joyous asses. To Spanish audiences of the time, clued in by the work’s title, this ludicrous role reversal between beasts of burden and impoverished men was clearly a play on the popular saying “Tu que no puedes, llévame à cuestas” (You who cannot, carry me on your back), a gibe against the nobility and clergy who heavily burdened the poor with taxes, high rents, and social restraints from which they spared themselves.

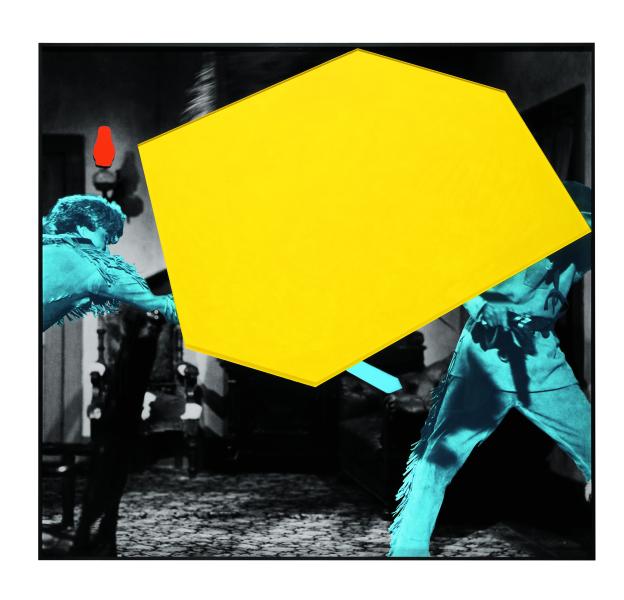

The telling of stories by commingling images with texts became omnipresent in Baldessari’s work starting in the mid-1960s. The title of the present exhibition, John Baldessari: Parables, Fables, and Other Tall Tales, hints directly at this aspect of his art, with one of the earliest works to be presented, Ingres and Other Parables (1972), drawing directly from what he saw in Goya’s work: here, he set each of ten photographs astride a short story, the two being loosely connected yet mutually empowering. To bridge international audiences for Ingres and Other Parables, Baldessari had each parable translated into French, German, and Italian, making the work available to diverse readers.

In 1999, Baldessari closed the circle, directly addressing Goya’s legacy in a body of work that he portrayed as an unequivocal investigation of the artist’s prints:

"I find the poetry and ambiguity [in Goya’s titles] intriguing because of the choice of words and phrasing, but also how the title does not relate specifically to the image. There is diffuseness and generality about them that allows them to stand on their own. They are rich. In this new work I use his titles or I invent Goyaesque titles and pair them with photographs I have taken. When the combination works best, neither photo nor title is prioritized; they are equally important and there is a moment of synthesis and equilibrium."

The use of language and images as a leveraging fulcrum is instrumental throughout Baldessari’s work. The show at Bozar highlights this unity, with his lasting desire to reach audiences on multiple platforms of engagement stemming from his curiosity about the intersections between overt and covert levels of meaning in art.