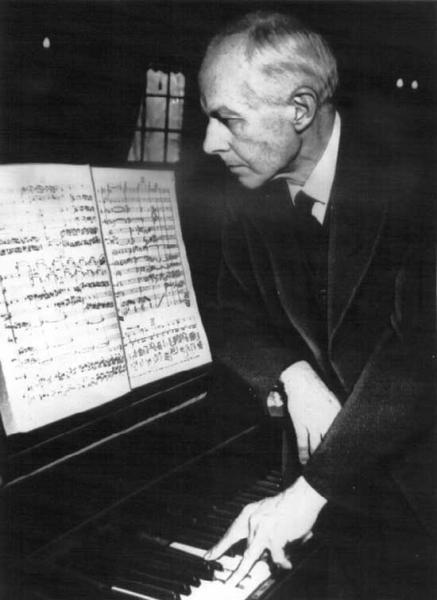

There exists a beautiful watercolor of Béla Bartók gazing with fascination at a fly on a flower. The portrait, painted by his cousin Ervin Voit, captures the essence of how we know Bartók: a shy lover of nature with a deep affection for the countryside and for the authentic music of the people who inhabited the rural regions of Hungary and Romania. A quiet observer with an extraordinary eye (and ear) for detail. He set out equipped with recording devices to document genuine peasant songs. He analyzed the music meticulously and produced detailed transcriptions. Almost instinctively, he wove these often centuries-old melodies into his own compositions. Sometimes he did so literally, but more often he composed new music permeated by the folk spirit he had come to know during his excursions. The scales, characteristic harmonies, instrumental timbres, and more—all these traits left their mark on the musical vocabulary of the Hungarian composer.

When hearing the opening measures of The Miraculous Mandarin, it is almost inconceivable that this gentle, nature- and people-loving man composed such a musical cacophony. Yet Bartók did here exactly what he did in his Hungarian-inflected music: he observed the world and colored his own musical style with those observations. Only this time, the world of The Miraculous Mandarin is not that of an innocent mayfly or a traditionally singing peasant family. It is an urban world in which lust and eroticism, seduction and deception, and above all fraud and criminality take center stage.

A difficult process

The Miraculous Mandarin was originally conceived as a pantomime, a wordless play. The story came from the pen of the Hungarian writer Melchior Lengyel. The ink was barely dry when Bartók began composing in 1917, and yet it would take until 1926 before the work premiered in Cologne. The turbulent political situation during and after the First World War played a major role in this delay. Bartók completed the piano version of the score but only began orchestrating it once he was certain a performance would take place. And that proved far from straightforward, as the unedifying subject matter generated little enthusiasm for production. Ultimately, the premiere took place in Cologne, paired with Bartók’s only opera, Duke Bluebeard’s Castle. This highly conservative and deeply Catholic city did not seem the most obvious setting for a pantomime about prostitution and murder, but it was the first opportunity to dust off the score that had been lying on the corner of Bartók’s desk for years.

The first performance was not a success. The audience—likely having formed its judgment in advance based on the announced storyline—soon erupted into turmoil. The entire company, Bartók included, was booed. There were no repeat performances, and the work was even banned by the mayor of Cologne. All this for a piece that Bartók would still regard many years later as his finest orchestral work! Two years later, the slightly shorter concert suite was first heard in Budapest. Only in 1945, after Bartók’s death, was the pantomime itself staged there as well.

The story

We find ourselves in a bustling city. According to some analysts, Bartók was inspired by the vibrancy of Paris, where he had stayed at least in 1905 and 1910, but the precise location remains unspecified in the story. In this city we encounter three criminals bent on robbing passersby. To this end, they enlist the services of Mimi, a beautiful young woman. She positions herself behind a window to lure unsuspecting men inside. The first victim is an old man, but he turns out not to have a penny to his name. The second victim, a handsome young fellow, also yields nothing. But as in any good story, the third time is the charm: the Miraculous Mandarin appears on the threshold—a wealthy Chinese man who gazes at the young woman with rapt fascination. The criminals strip him of his riches, but they fail to drive him away like the other men. Even their desperate attempts to kill him prove futile. A tense chase scene leads to the ultimate violent confrontation. Yet even when they stab him repeatedly and hang him from a ceiling lamp, the man refuses to die. At a surreal climax, he even begins to emit an eerie green light. Only after the young woman finally gives in and allows him to satisfy his desires does he succumb to his wounds.

The music

In this score we encounter a remarkable combination of three facets of Bartók’s musical language. As in many of his earlier works, the influence of Debussy is still perceptible. Bartók paints orchestral sounds with an exquisitely refined brush and, like the French Impressionist, succeeds in evoking vivid images. At the same time, we hear just how relentlessly modern Bartók could be as a composer. He does not shy away from dissonance, employs a vibrant rhythmic language, and does not hesitate to translate the raw emotions and aggression of the story into violent sounds. A third aspect, omnipresent in Bartók’s music, is the influence of folk music. Although this score contains no clear examples of folk melodies or dances such as the frequently cited verbunkos, Bartók’s language is nonetheless permeated with musical ingredients drawn from folk traditions. Indeed, it is precisely these non-classical elements that render his musical language so modern.

A clear example can be heard during the first seduction scene. The woodwinds play a melody in parallel major seconds—that is, the same melody played a single pitch apart, something impossible within classical tonality. It sounds dissonant and modern, yet Bartók had in fact encountered this technique in Yugoslav folk music. Later, in the Concerto for Orchestra, he would apply the same technique in a duet for two trumpets.

In a wordless pantomime, the music also makes the story visible. The overture is a highly animated tone painting of urban bustle, including car horns and street chaos. In a letter to his wife, Bartók wrote of this opening: “If I succeed, it will be hellish music. It will sound like a terrible pandemonium.” When the young woman sets out to seduce, she is invariably accompanied by sensual clarinet melodies. The Mandarin’s arrival, by contrast, is announced by pentatonic, Eastern-sounding themes. The final chase scene is conceived as a modern variant of a fugue (aptly derived from the Latin fugere, to flee): a nerve-racking passage of music in which one can almost feel the adrenaline coursing through the characters.

After Duke Bluebeard’s Castle and The Wooden Prince, The Miraculous Mandarin is Bartók’s final work for the stage. The composer was disappointed that the music encountered so much resistance, while The Wooden Prince—a score with which he himself was less satisfied—became highly popular. Composers, after all, do not get to choose which of their works will achieve the greatest success.

On 8 February at 7pm, Klaas Coulembier will give a bilingual (NL-FR) introduction to this iconic work in the Horta Hall.